Black Art History

Exploring the lives and legacies of Black artists who shaped art history and culture. Each week during Black History Month, we highlight trailblazing figures whose works continue to inspire and redefine the creative landscape.

Discover their stories, learn their impact, and join the conversation. Read the history. Give us feedback.

Edward Bannister: The First Black Artist to Win a National Art Award

He made history as the first Black artist to win a national award—only to be shut out of the ceremony. This is Edward Bannister’s story of talent and perseverance.

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Palmer River, 1885, oil on canvas, private collection

In 1876, Edward Mitchell Bannister became the first Black artist to win a national art award when his painting Under the Oaks took first place at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. But when the judges discovered the artist was Black, he faced backlash and exclusion from the award ceremony. The decision to let Bannister keep the prize was a groundbreaking moment, yet it was just one chapter in his larger legacy.

Despite systemic racism and exclusion from formal artistic institutions, Bannister established himself as a leading landscape painter and a key figure in 19th-century American art. His life’s work not only challenged racial barriers but also shaped the future of Black artistic communities in the U.S.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

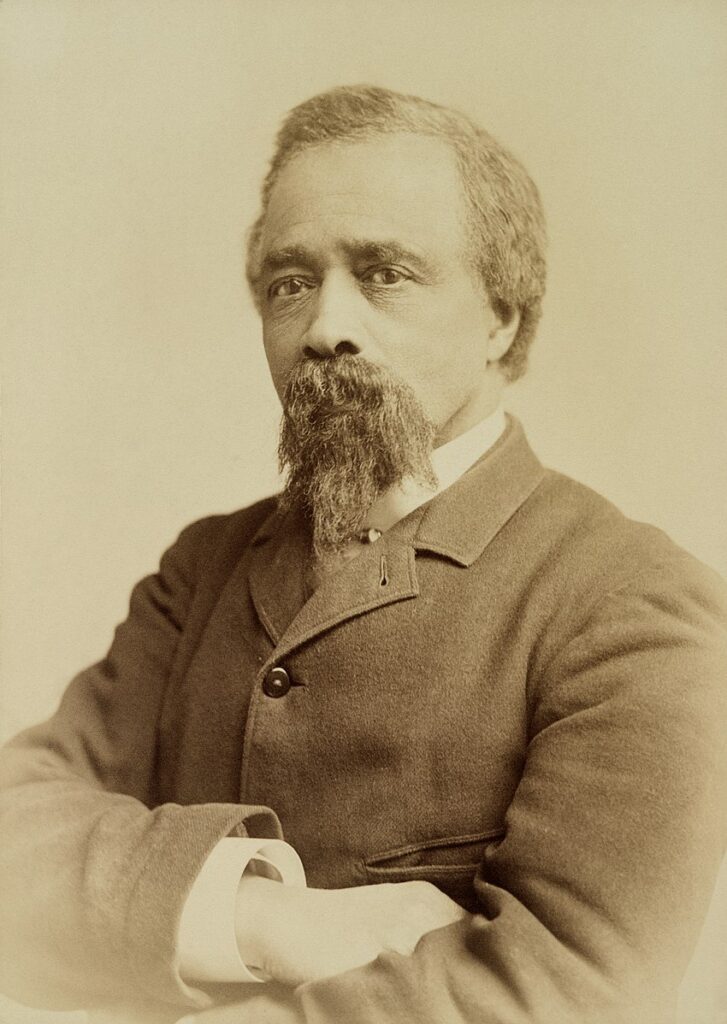

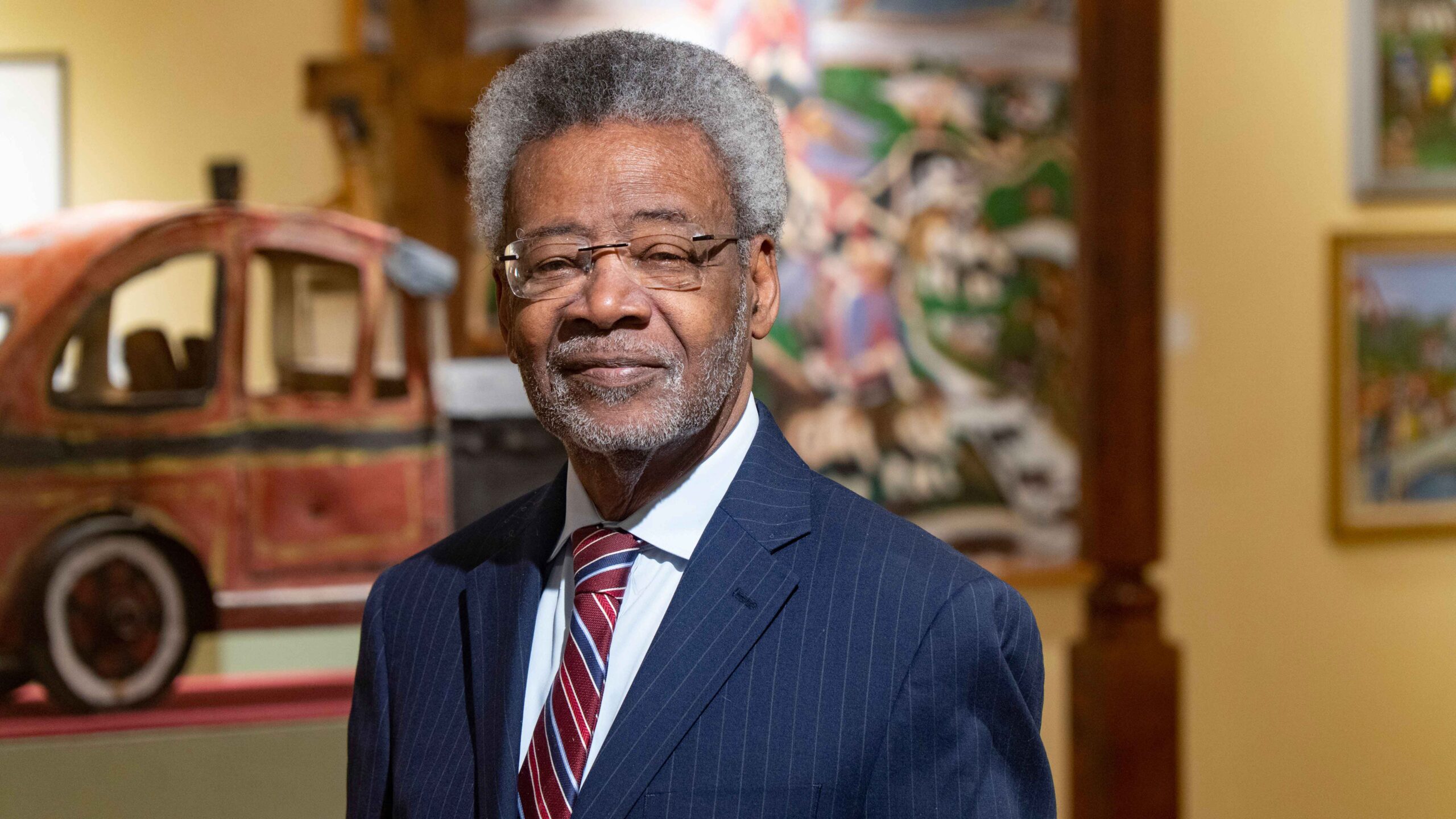

Albumen silver print of Edward Mitchell Bannister in a cabinet card mount

Albumen silver print of Edward Mitchell Bannister in a cabinet card mount

Edward Bannister was born in 1828 in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada. Orphaned at a young age, he moved to Boston, Massachusetts, in the 1840s, where he worked various jobs—including as a barber and a ship steward—while nurturing his love for art.

Unlike many successful artists of his time, Bannister was mostly self-taught. Formal training opportunities were denied to him because of his race, but he educated himself by studying art books and works on display at the Boston Athenæum, one of the city’s premier cultural institutions.

One of his biggest early influences was Robert S. Duncanson, a pioneering Black landscape painter who had achieved international success. Seeing a Black artist succeed on that level inspired Bannister to pursue a professional career despite the obstacles ahead.

The Centennial Exhibition Controversy

Bannister’s breakthrough came in 1876 when he submitted Under the Oaks to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, the first official World’s Fair in the U.S. His painting won first prize in the category of painting, but when officials discovered he was Black, an uproar ensued.

While the judges ultimately upheld their decision, Bannister was still barred from attending the award ceremony. To make matters worse, Under the Oaks has since been lost, leaving only historical accounts to confirm its impact.

Despite this racist backlash, the victory established Bannister’s reputation and helped him gain more commissions and recognition in the American art world.

Bannister’s Artistic Style and Philosophy

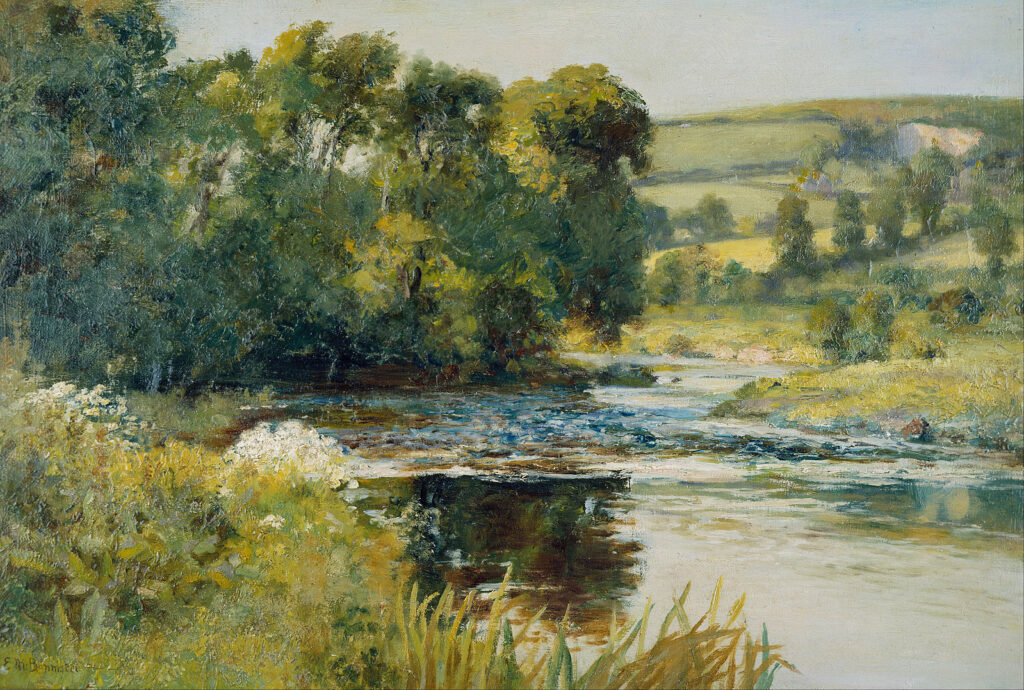

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Streamside, 1870, oil on canvas

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Streamside, 1870, oil on canvas

Unlike many Black artists of his time who focused on portraiture or scenes of Black life, Bannister chose to specialize in landscape painting. Inspired by the Hudson River School and the French Barbizon School, he created tranquil, atmospheric depictions of the natural world, often focusing on pastoral scenes, sunsets, and rural life.

His work was deeply influenced by Tonalism, a movement that emphasized mood, color harmony, and soft, diffused light. Many of his paintings feature earthy tones and muted palettes, inviting viewers into serene, contemplative spaces.

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Untitled (Landscape with Man on Horse), 1884, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Untitled (Landscape with Man on Horse), 1884, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Some critics have debated why Bannister avoided painting explicitly Black subjects. One perspective is that he sought to prove that Black artists could succeed in mainstream artistic traditions. Others argue that his landscapes were a form of quiet resistance, creating beauty in a world that denied him recognition.

A Leader in Providence’s Art Scene

After marrying Christiana Carteaux Bannister, a successful Black businesswoman and abolitionist, Bannister moved to Providence, Rhode Island, in the late 1860s. There, he became a leader in the city’s art scene.

In 1880, he co-founded the Providence Art Club, one of the oldest art clubs in the United States. Although he helped build the institution, he still faced racial discrimination, often being sidelined in exhibitions and events. Nevertheless, he remained a mentor and advocate for other artists, especially young Black creatives.

Despite his accomplishments, Bannister’s career was still constrained by racism. Unlike white artists of his era, he struggled to secure widespread financial success or major institutional backing. Still, he remained committed to his craft until his death in 1901.

Edward Mitchell Bannister, The Drinking Pool (man in cart with oxen at pool), 1895, oil on canvas

Edward Mitchell Bannister, The Drinking Pool (man in cart with oxen at pool), 1895, oil on canvas

Today, Edward Bannister’s work is finally being recognized as a critical part of American art history. His landscapes not only showcase technical skill but also tell the story of a Black artist who refused to be erased.

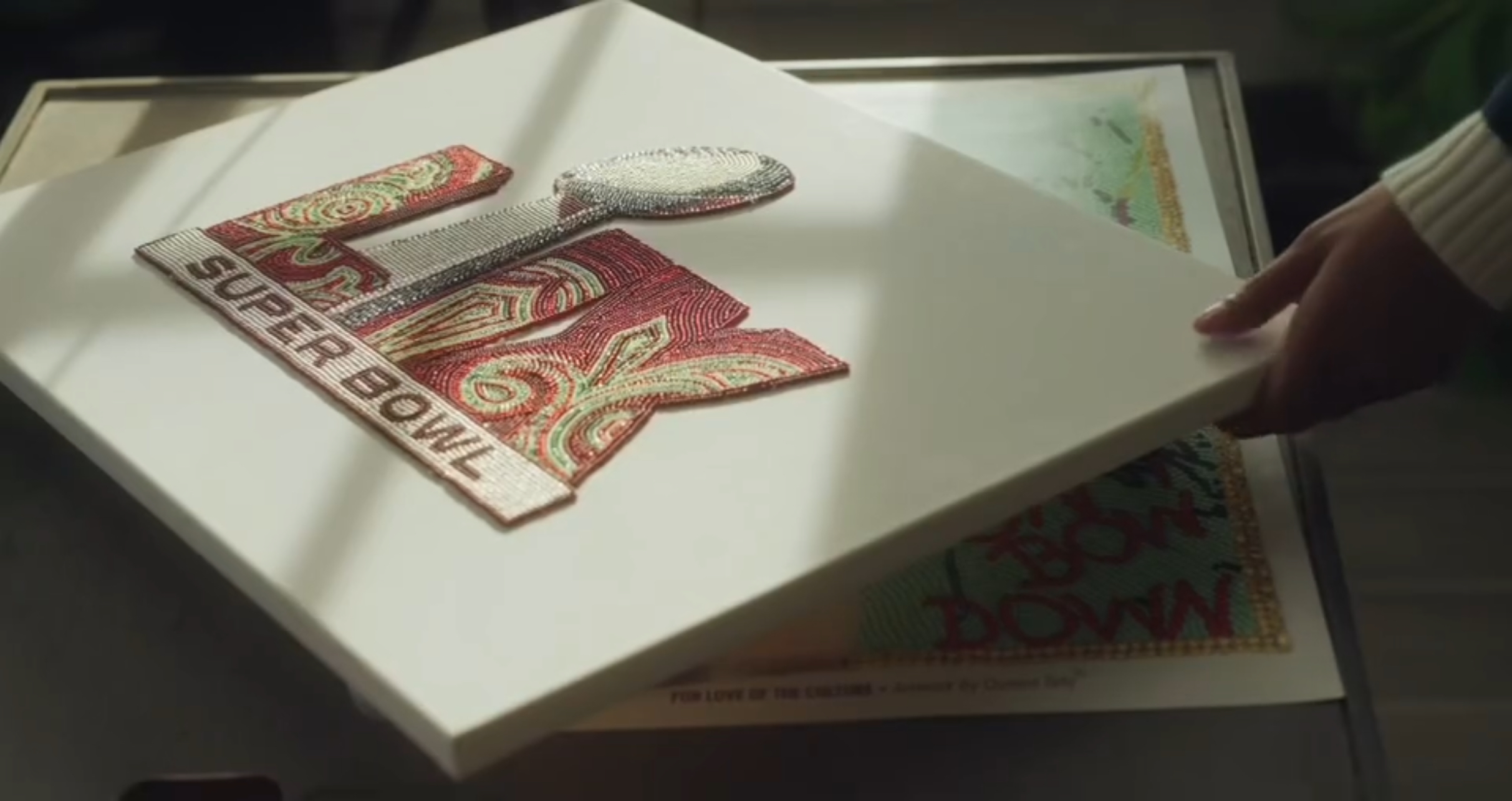

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’

Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’ Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month

Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball

The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

SUBMIT

CONNECT

Privacy Policy Copyright © 2025 Black Art Magazine is proudly powered by KVBOND