Black Art History

Exploring the lives and legacies of Black artists who shaped art history and culture. Each week during Black History Month, we highlight trailblazing figures whose works continue to inspire and redefine the creative landscape.

Discover their stories, learn their impact, and join the conversation. Read the history. Give us feedback.

Edmonia Lewis: The First Black and Native American Sculptor to Gain Fame

How Lewis overcame racism, sexism, and historical neglect to secure her place in art history—and why her neoclassical sculptures remain revolutionary.

Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867, Carrara marble, 106 x 57.2 cm, 31.4 cm in diameter (Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A Chisel Against Erasure

The marble tells a story. Chiseled into its surface, a newly emancipated Black man rises triumphantly, his broken shackles still clinging to his wrists. Beside him, a Black woman kneels in prayer, her hands clasped in gratitude—but her chains remain, subtly intact. This is Forever Free (1867), one of Edmonia Lewis’ most powerful sculptures, and a rare depiction of Black freedom by a Black artist in the 19th century. Unlike the sentimentalized, passive figures sculpted by white artists of the time, Lewis’ work exudes agency, strength, and complexity.

But for more than a century, her name was nearly forgotten. Despite international fame in her lifetime, Lewis was erased from mainstream art history, her sculptures lost or scattered, her story left incomplete. Today, art historians, curators, and Black artists are reclaiming her legacy, ensuring her work—and her defiant spirit—are remembered.

The Road to Defying Erasure

Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis

Born in 1844 to a free Black father and an Ojibwe mother, Edmonia Lewis’ early life was marked by both struggle and resilience. Orphaned by the age of nine, she lived with her mother’s Ojibwe relatives in upstate New York, where she learned beadwork and other traditional crafts. But she longed for something more.

With the help of her older brother, Lewis enrolled at Oberlin College in Ohio—one of the few schools that admitted Black women. There, she found herself immersed in a progressive yet deeply racist environment. In 1862, she was falsely accused of poisoning two white classmates. Though no evidence linked her to the crime, a violent mob attacked her, beating her so severely that she barely survived. Soon after, she was expelled from Oberlin under dubious circumstances.

The experience could have ended her artistic ambitions, but Lewis refused to be silenced. She moved to Boston, where she sought out the sculptor Edward Augustus Brackett, known for his busts of abolitionist figures. Under his mentorship, Lewis began carving portraits of Black leaders, including John Brown and Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. These works gained the attention of abolitionist patrons, and with their support, she did something extraordinary: she financed her own journey to Rome in 1865.

“I was practically driven to Rome in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color,” Lewis later said.

The Radical Beauty of Her Sculptures

Edmonia Lewis, Old Arrow Maker, modeled 1866, carved 1872, carved marble, 21 1⁄2 x 13 5⁄8 x 13 3⁄8 in. (54.5 x 34.5 x 34.0 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Joseph S. Sinclair, 1983.95.182

Edmonia Lewis, Old Arrow Maker, modeled 1866, carved 1872, carved marble, 21 1⁄2 x 13 5⁄8 x 13 3⁄8 in. (54.5 x 34.5 x 34.0 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Joseph S. Sinclair, 1983.95.182

Why Neoclassicism? A Subversive Choice

In Rome, Lewis embraced neoclassicism—a style dominated by white European men. But her approach was anything but conventional. Neoclassical art often stripped subjects of their contemporary political context, idealizing them in smooth, timeless marble. Lewis used this aesthetic to her advantage, gaining respect in elite art circles while subverting expectations. She sculpted Black and Indigenous subjects in neoclassical form, forcing viewers to confront histories they preferred to ignore.

Her themes centered on freedom, resistance, and identity—issues deeply personal to her own experience. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Lewis rarely depicted white patrons or mythological figures; she focused instead on Black liberation and biblical women of struggle, like Hagar.

Edmonia Lewis, Hagar, 1875, carved marble, 52 5/8 x 15 1/4 x 17 1/8 in. (133.6 x 38.8 x 43.4 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., 1983.95.178

Edmonia Lewis, Hagar, 1875, carved marble, 52 5/8 x 15 1/4 x 17 1/8 in. (133.6 x 38.8 x 43.4 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., 1983.95.178

A Closer Look: Forever Free

One of Lewis’ most celebrated works, Forever Free (1867), commemorates the Emancipation Proclamation. At first glance, it appears to celebrate the newly won freedom of Black Americans. But a closer examination reveals something more layered.

Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867, Carrara marble, 106 x 57.2 cm, 31.4 cm in diameter (Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867, Carrara marble, 106 x 57.2 cm, 31.4 cm in diameter (Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The male figure stands tall, proud, and liberated, his broken chains emphasizing his newfound freedom.

The female figure, however, is still kneeling. Her wrists are free, but remnants of her chains remain. This subtle detail suggests that freedom—especially for Black women—was still incomplete.

The figures’ idealized, classical forms made the sculpture more palatable to white audiences while allowing Lewis to embed a deeper, radical message.

Art historian Kirsten Pai Buick notes, Forever Free challenges the “passive slave” trope common in 19th-century abolitionist art. Instead of depicting Black figures as helpless or reliant on white saviors, Lewis presents them as self-possessed, actively claiming their own freedom.

The Death of Cleopatra: A Bold Rebellion

Edmonia Lewis, The Death of Cleopatra, carved 1876, marble, 63 x 31 1/4 x 46 in. (160.0 x 79.4 x 116.8 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Historical Society of Forest Park, Illinois, 1994.17

Edmonia Lewis, The Death of Cleopatra, carved 1876, marble, 63 x 31 1/4 x 46 in. (160.0 x 79.4 x 116.8 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Historical Society of Forest Park, Illinois, 1994.17

Perhaps Lewis’ most daring work, The Death of Cleopatra (1876), defied every artistic convention of its time. Unlike the sentimental, romanticized portrayals of Cleopatra by European artists, Lewis sculpted her as a powerful, tragic ruler—her body slumped on her throne, lifeless yet commanding. The piece shocked viewers at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, with critics calling it “ghastly.”

Over time, the sculpture disappeared, eventually being found in a Chicago storage yard. Its rediscovery in the 20th century reignited interest in Lewis’ work, proving just how easily Black artists can be erased from history.

Forgotten, Then Found

Despite her brilliance, Lewis faded from public consciousness after her death in 1907. Many of her sculptures were lost, and for decades, even basic details about her life remained uncertain.

The rediscovery of The Death of Cleopatra in the 1980s was a turning point. Scholars like Marilyn Richardson began piecing together her story, bringing long-overdue recognition to her work. Today, Lewis’ sculptures are housed in major institutions like the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2022, the U.S. Postal Service honored her with a commemorative stamp—a long-overdue acknowledgment of her contributions.

Why Edmonia Lewis Still Matters

Lewis’ story is one of perseverance, artistry, and defiance. At a time when Black artists were barely acknowledged, she carved a place for herself—literally and figuratively.

Her work challenges the assumption that Black artistry is a modern phenomenon. It forces us to reconsider who has been left out of art history and why. And in an era where Black artists are still fighting for recognition, her legacy remains deeply relevant.

“There is nothing so beautiful as the free forest,” Lewis once said. “To catch a fish when you are hungry, cut the boughs of a tree, make a fire, and roast the fish at once. That is happiness.”

Like the forest, Lewis’ legacy refused to be tamed, defined, or erased. And today, her name and work stand forever free.

What’s Next for Lewis’ Legacy?

Black artists today continue to grapple with visibility, access, and the rewriting of history. How do you see Lewis’ legacy reflected in today’s art world? Drop your thoughts in the comments, and let’s continue the conversation.

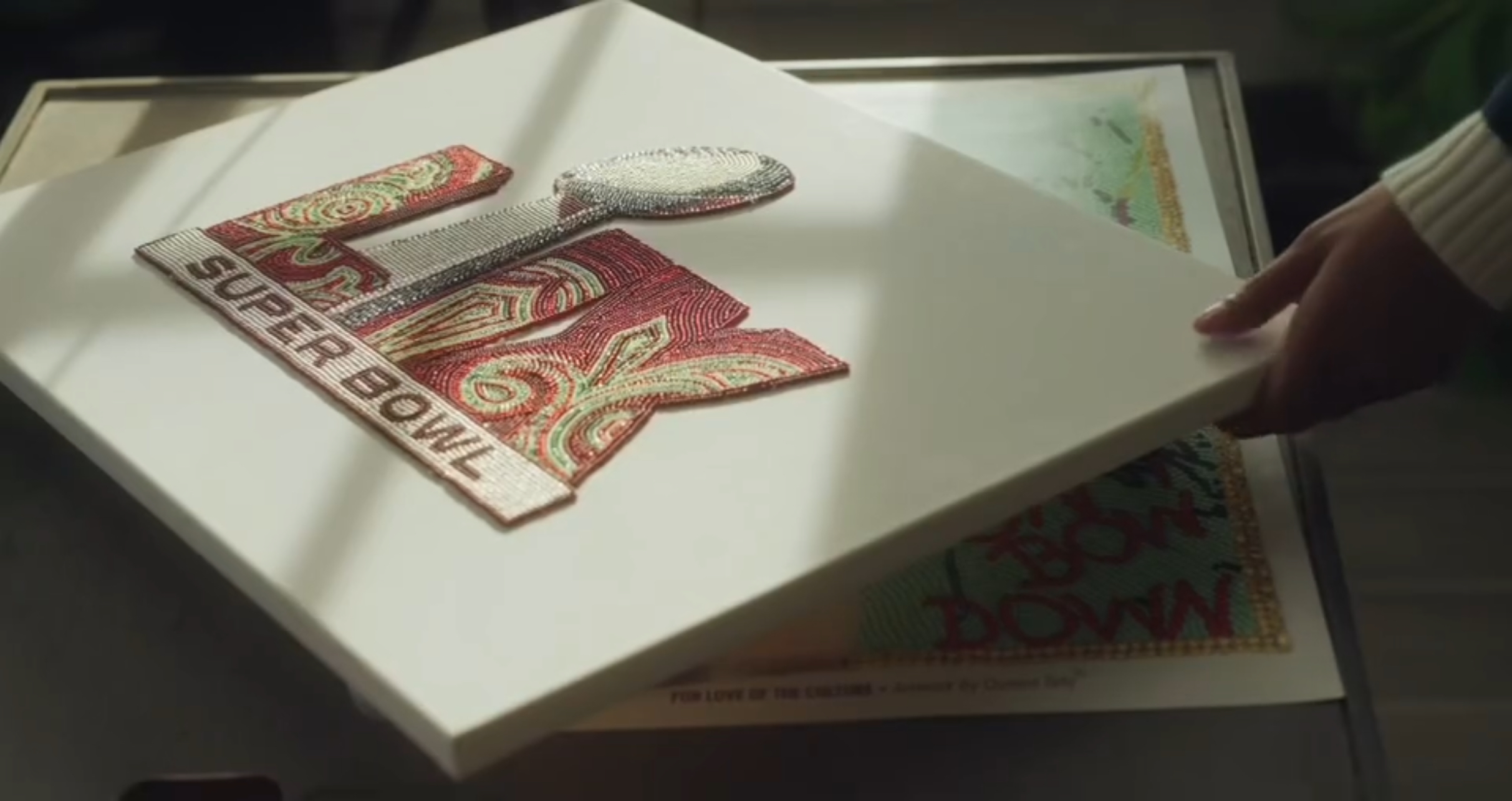

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’

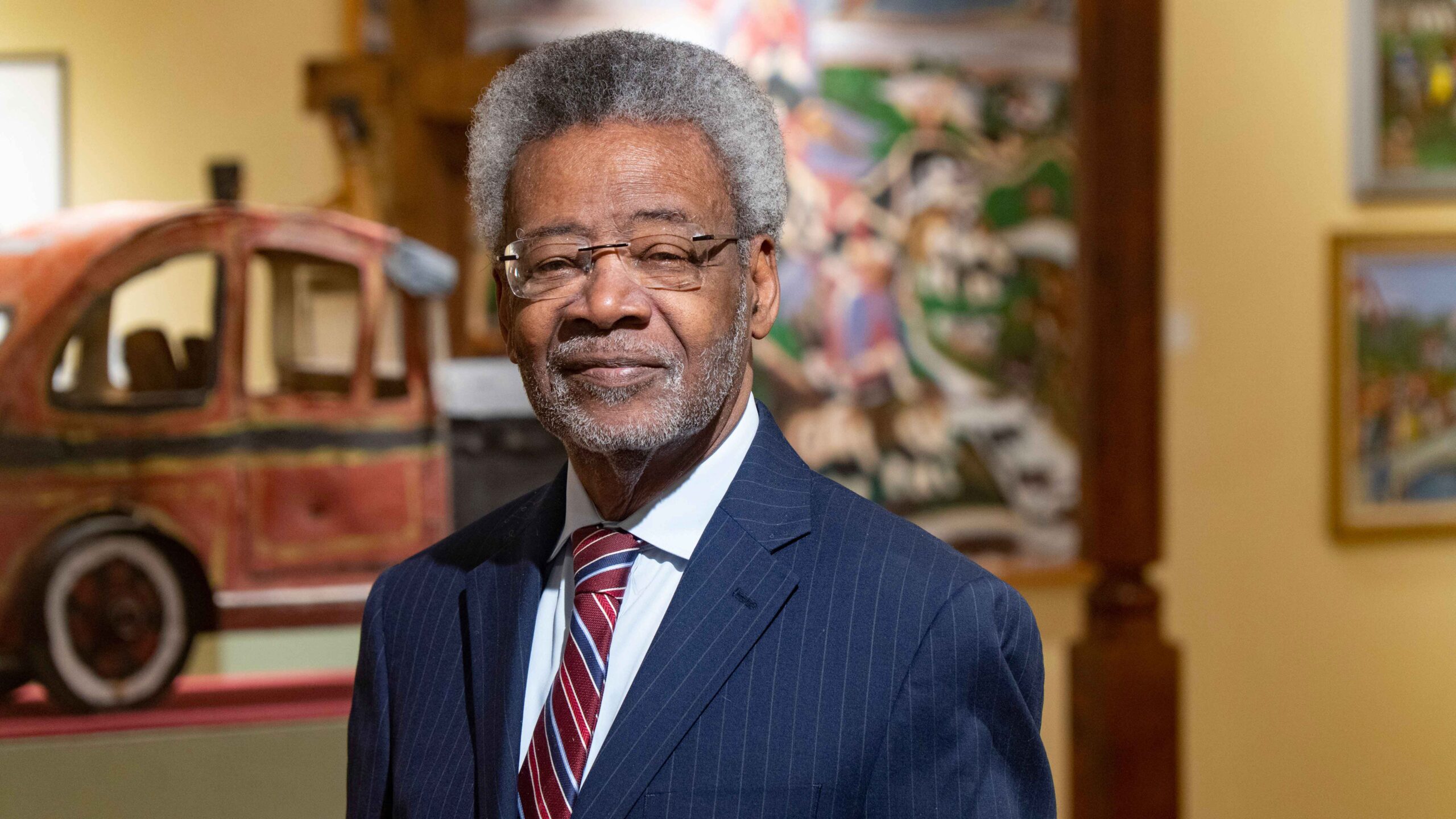

Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’ Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month

Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball

The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

SUBMIT

CONNECT

Privacy Policy Copyright © 2025 Black Art Magazine is proudly powered by KVBOND