Creative Freedom vs. Copyright: The Legal Standoff Between Deborah Roberts and Lynthia Edwards on Collage Art

A copyright dispute between Deborah Roberts and Lynthia Edwards raises complex questions on originality, influence, and artistic freedom in the world of collage.

The recent legal dispute between contemporary artists Deborah Roberts and Lynthia Edwards has set the art world buzzing with questions about creativity, influence, and originality. This case, which centers on the use of similar collage compositions, marks a broader trend in the art world where artists are increasingly turning to copyright protections to safeguard their work. But as copyright enters the realm of collage—an art form rooted in reimagining and recombining—many are left wondering where the line should be drawn.

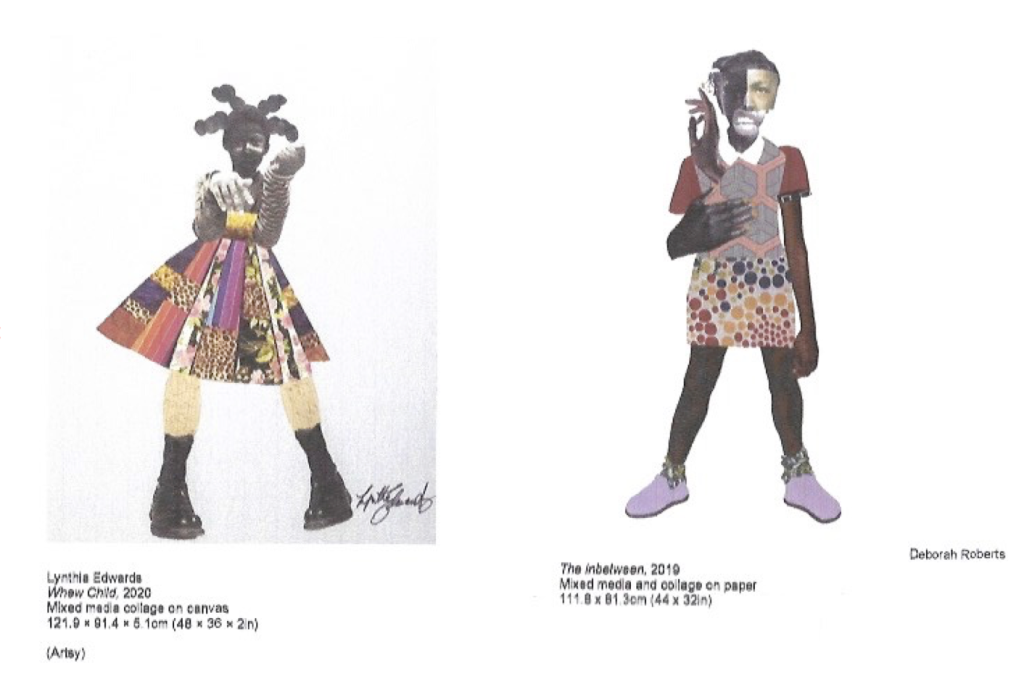

Roberts and Edwards both work in collage, a medium that naturally layers elements from various sources, often blending photographic pieces with drawn or painted ones. Their recent legal clash is over compositions that present figures against minimalist, often blank, backgrounds. Roberts argues that Edwards’ work is too close to her own—a similarity that has sparked a conversation over whether the art world should embrace these overlapping styles as an extension of a shared aesthetic or draw hard lines to protect individual approaches.

A comparison of work by Edwards (left) and Roberts (right) from court documents.

The core of the disagreement highlights a broader issue: as artists build on shared cultural narratives, at what point does stylistic similarity cross the line into copyright infringement? Collage art, perhaps more than most other forms, thrives on the remixing of materials and ideas, raising questions about whether strict copyright enforcement helps or hinders its evolution.

Historical Movements as Shared Style

To consider this issue fully, it’s helpful to look back at how art movements have historically developed. Take Impressionism, for instance—an art movement built on shared techniques and themes, where artists like Monet, Degas, and Renoir collectively shaped a style that would influence generations. No one artist could claim the technique of capturing light and movement on canvas as proprietary, even as they each built unique perspectives within the movement’s boundaries. Artists were building on one another’s work, not competing over style ownership, and their collective explorations eventually birthed post-Impressionism and new artistic frontiers.

One might ask, why can’t today’s artists view stylistic overlap with the same open-mindedness? Shouldn’t the development of similar collage techniques, such as those used by Roberts and Edwards, be seen as the foundation of a possible movement? In an era where collage art and digital media increasingly overlap, it’s only natural that artists will take inspiration from similar sources and experiment with familiar compositions.

What Makes a Composition Original?

This case also raises the question: what actually defines an “original” composition? Both Roberts and Edwards use figures on minimalist backgrounds—arguably, a straightforward choice that provides viewers a focused view of the subject without visual distractions. However, is a figure on a plain background something that can be copyrighted? Wouldn’t it be like photographers claiming headshots or landscapes as their proprietary compositions? For many, this stylistic choice is a compositional starting point, not an infringement. While both artists are unique in their own ways, some question whether it’s reasonable to claim ownership over such a broad concept.

The Commercialization of Style

With art becoming increasingly commercialized, some artists may feel pressure to protect what they see as their brand—a style they worked hard to develop and make recognizable. It’s understandable: reaching audiences and achieving financial stability in the art world is no easy feat, and sometimes style becomes synonymous with success. But when artists resort to copyright litigation to prevent others from adopting similar approaches, we might be stepping into territory where art begins to resemble a business rivalry rather than creative exploration.

Some might argue that instead of using copyright law as a shield, artists could view shared style as a form of creative solidarity. Shouldn’t an artist who spearheads a particular look feel honored when others adopt similar approaches? After all, when one artist reaches a larger audience, they may simply have a more effective way of connecting with viewers, not necessarily a more original one.

Final Thoughts

In the case of Roberts and Edwards, both artists are part of a cultural dialogue, each contributing unique voices to the larger narrative of Black identity, history, and expression through collage. While copyright law has a role in protecting artists, it’s worth questioning whether such protections should also consider the nature of art as a communal process. Could overly strict copyright laws ultimately stifle the creativity they aim to protect?

This case leaves open questions that will likely arise again, especially in the collage community, where shared materials and influences can easily overlap. As art audiences, we’re invited to consider what we value most: is it the authenticity of individual style, or the collaborative spirit of artistic evolution?

What’s your take? Join the conversation on copyright and creativity—we’d love to hear your thoughts.

Source: ArtNews

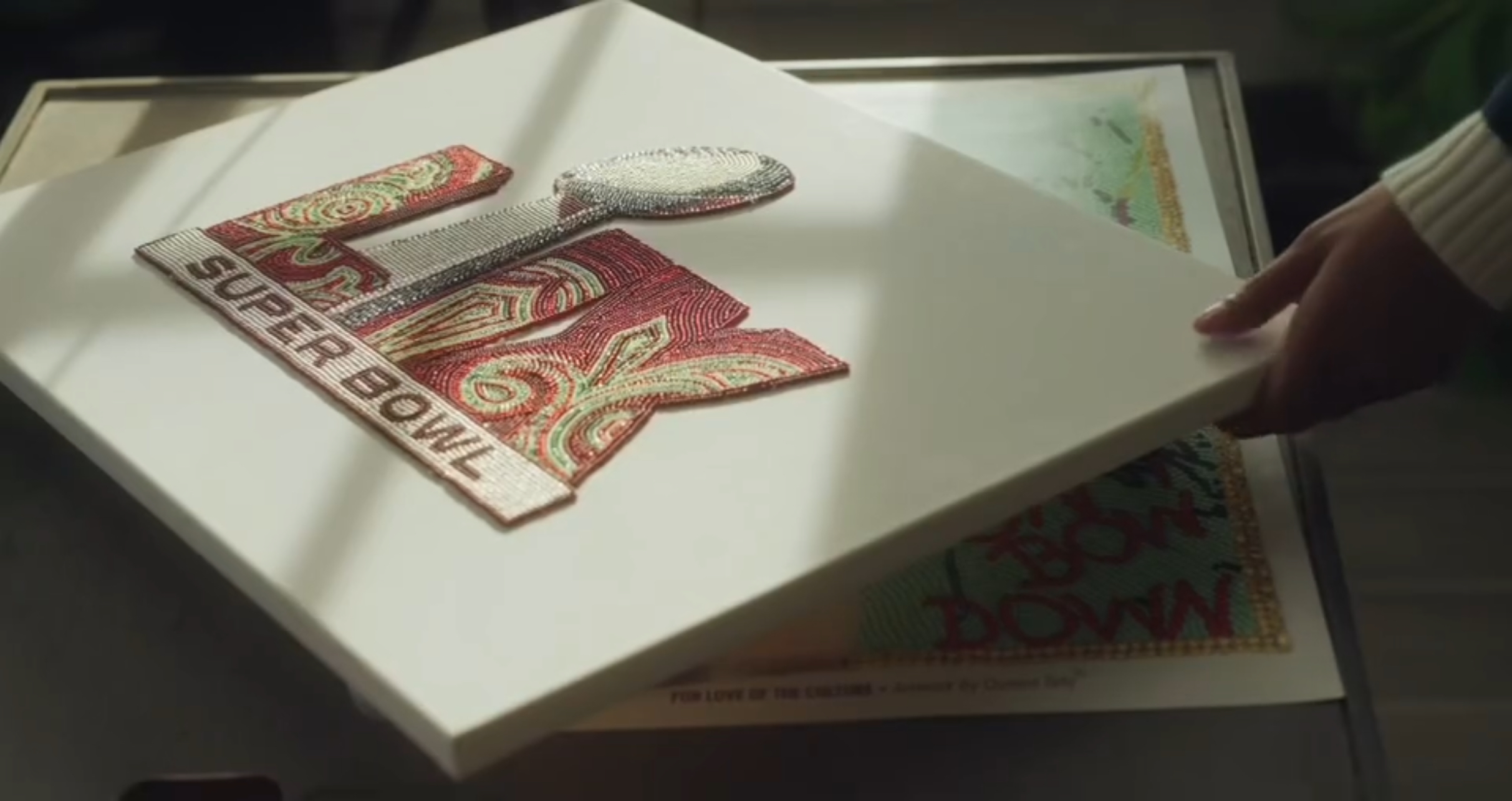

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’

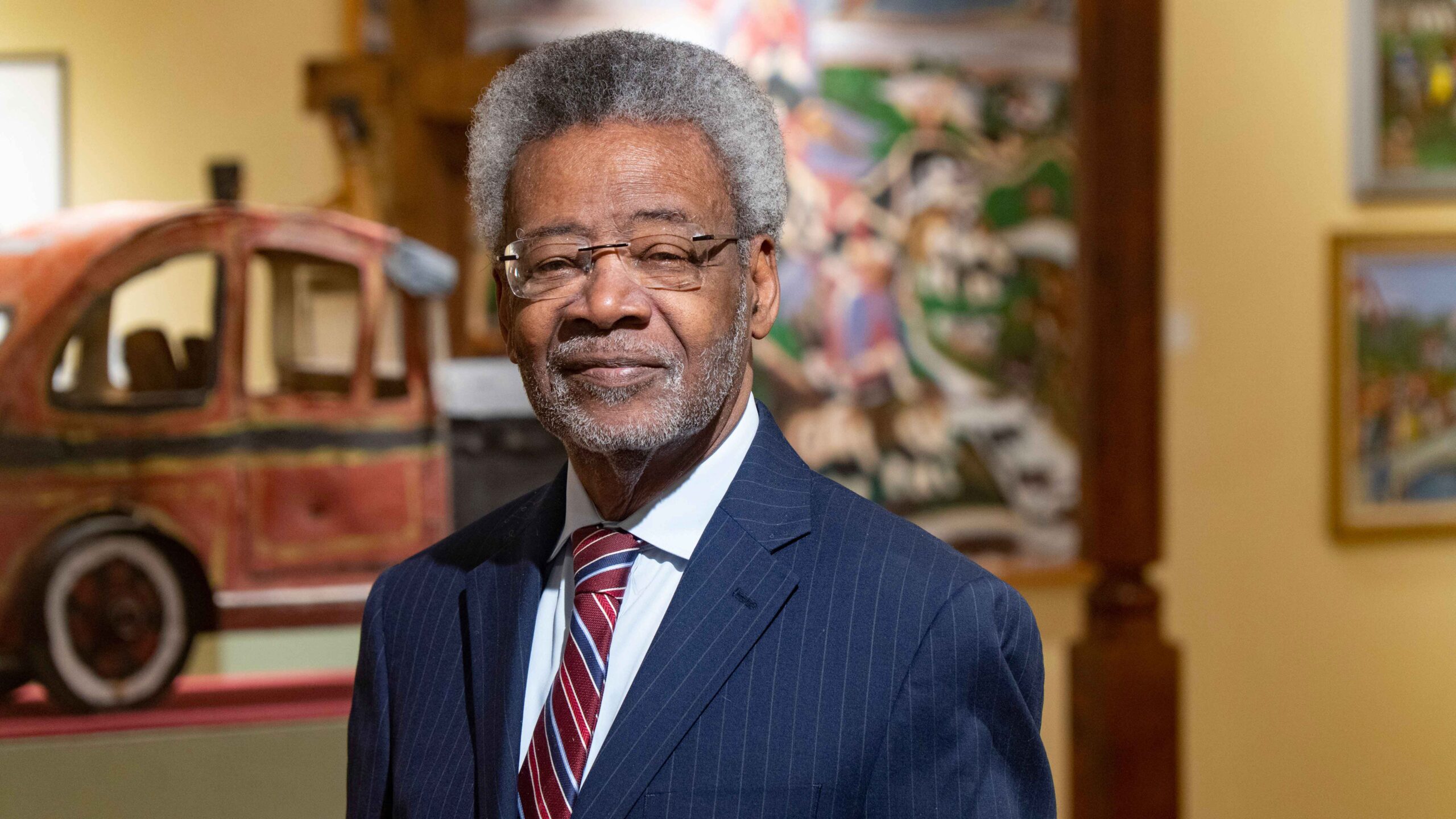

Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’ Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month

Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball

The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator