Black Art History

Exploring the lives and legacies of Black artists who shaped art history and culture. Each week during Black History Month, we highlight trailblazing figures whose works continue to inspire and redefine the creative landscape.

Discover their stories, learn their impact, and join the conversation. Read the history. Give us feedback.

Barkley Hendricks: Pioneering Black Portraiture with Style and Power

With striking portraits that blended classical technique with modern Black culture, Barkley Hendricks changed the way Black identity is seen in art forever.

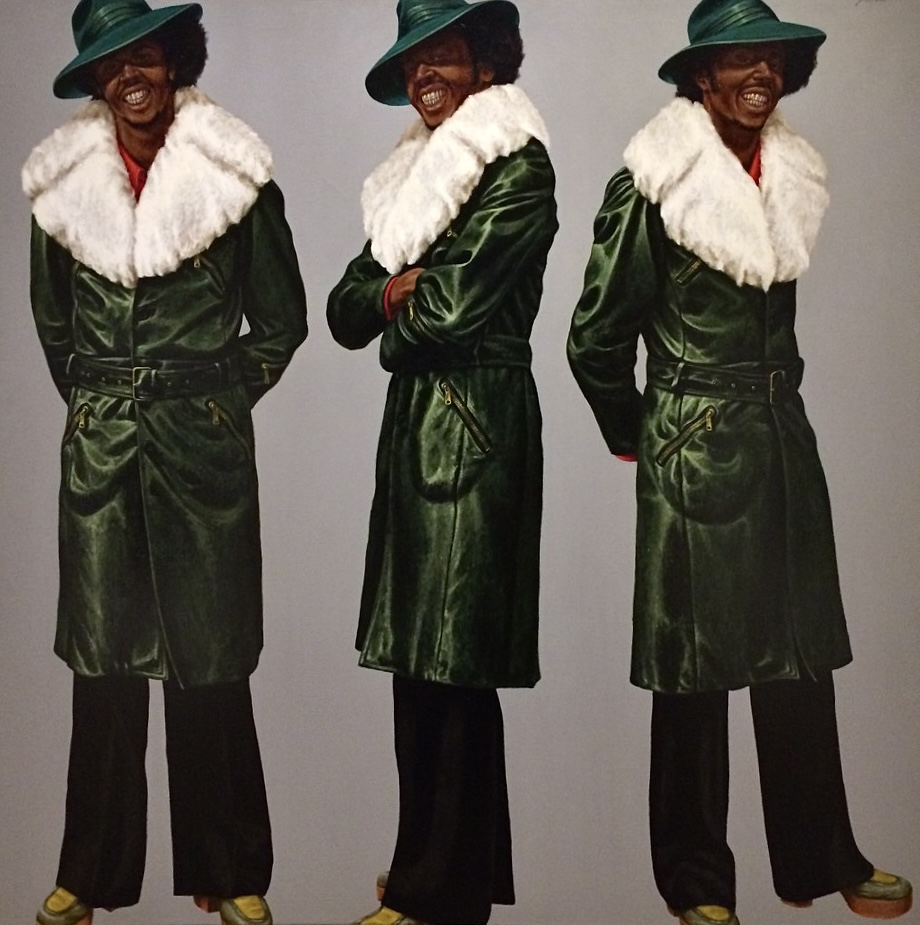

Barkley L. Hendricks, Steve, 1976, Oil, acrylic, and Magna on linen canvas. 72 × 48 in. (182.9 × 121.9 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art.

Barkley Hendricks didn’t just paint portraits—he created icons. With a palette that mixed Renaissance realism with the swagger of Black cool, he turned everyday people into larger-than-life figures. His work challenged the art world’s long-standing erasure of Black presence, leaving behind a legacy that continues to shape contemporary art today.

The Man Behind the Portraits

Born in 1945 in Philadelphia, Barkley L. Hendricks grew up in an era where Black faces were rarely seen in the Western art canon. While studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) and later Yale University, Hendricks became acutely aware of this absence. Instead of waiting for representation, he took matters into his own hands.

Influenced by classical European portraiture, the Old Masters, and the bold compositions of artists like Diego Velázquez and Édouard Manet, Hendricks began painting portraits of Black men and women with the same grandeur and reverence as historical aristocrats. But instead of powdered wigs and lavish robes, his subjects wore afros, leather jackets, sunglasses, and dashikis—contemporary symbols of Black power and self-expression.

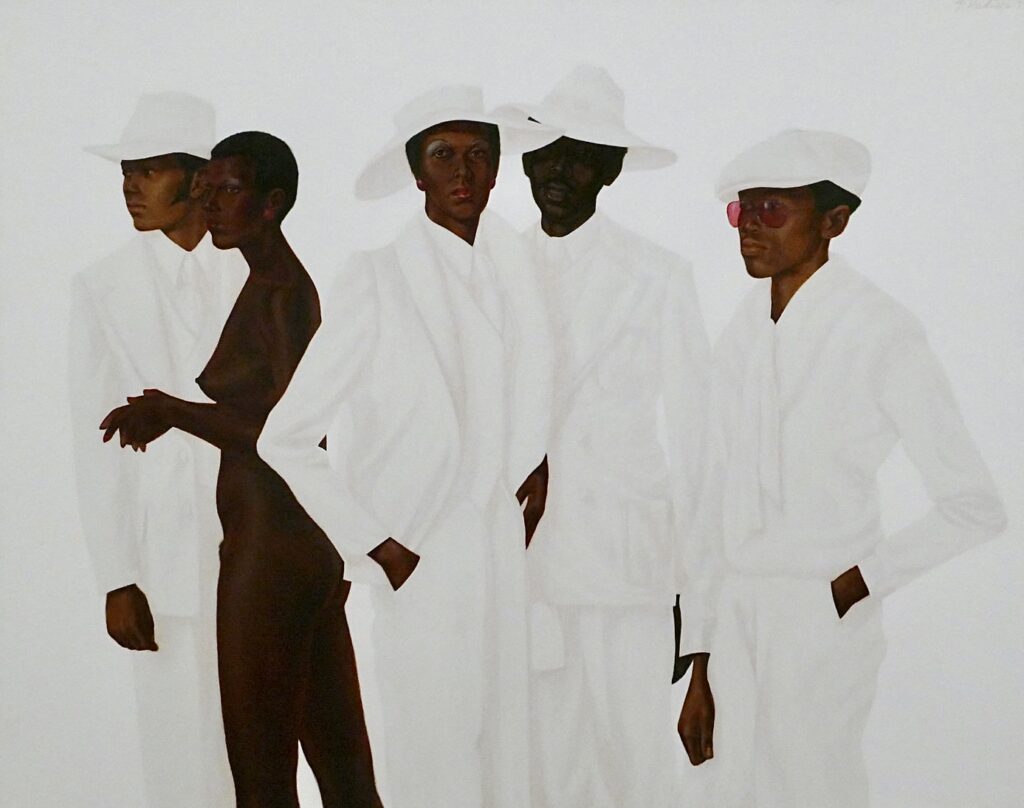

Barkley L. Hendricks, Northern Lights, 1976. Photo: Allison Meier, CC BY-SA 2.0

Barkley L. Hendricks, Northern Lights, 1976. Photo: Allison Meier, CC BY-SA 2.0

One of his most famous paintings, Lawdy Mama (1969), features a Black woman with a halo-like gold background, referencing both Byzantine iconography and the everyday beauty of Black women. By merging art historical traditions with modern Black culture, Hendricks sent a clear message: Black people are worthy of admiration, celebration, and legacy.

The Swagger of Black Cool

Hendricks’ work wasn’t just about representation—it was about attitude. His subjects stare directly at the viewer, exuding confidence, defiance, and self-assurance. They are not passive objects of observation but active participants in their own image-making.

Take Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris (1972), a full-length portrait of a man dressed in an all-white suit and hat, standing against a stark white background. His posture, style, and gaze suggest that he knows exactly who he is and that the world better take notice. This is what Hendricks captured best—the spirit of Black cool.

His work directly influenced later generations of artists, from Kehinde Wiley to Mickalene Thomas, who continue to challenge traditional portraiture and redefine Black presence in art.

Barkley L. Hendricks, “What’s Going On”, 1974. Photo: Loz Pycock, CC BY-SA 2.0

Barkley L. Hendricks, “What’s Going On”, 1974. Photo: Loz Pycock, CC BY-SA 2.0

A Legacy That Lives On

Despite his impact, Hendricks’ work was underappreciated for much of his career. It wasn’t until later in life that he received widespread recognition, with major retrospectives celebrating his contributions to contemporary art. His influence can now be seen in museums, galleries, and even popular culture, from music to fashion editorials.

Barkley Hendricks passed away in 2017, but his work remains as fresh and powerful as ever. His portraits continue to demand attention, reminding us that Black identity is not monolithic—it is regal, rebellious, everyday, extraordinary, and, above all, unapologetically present.

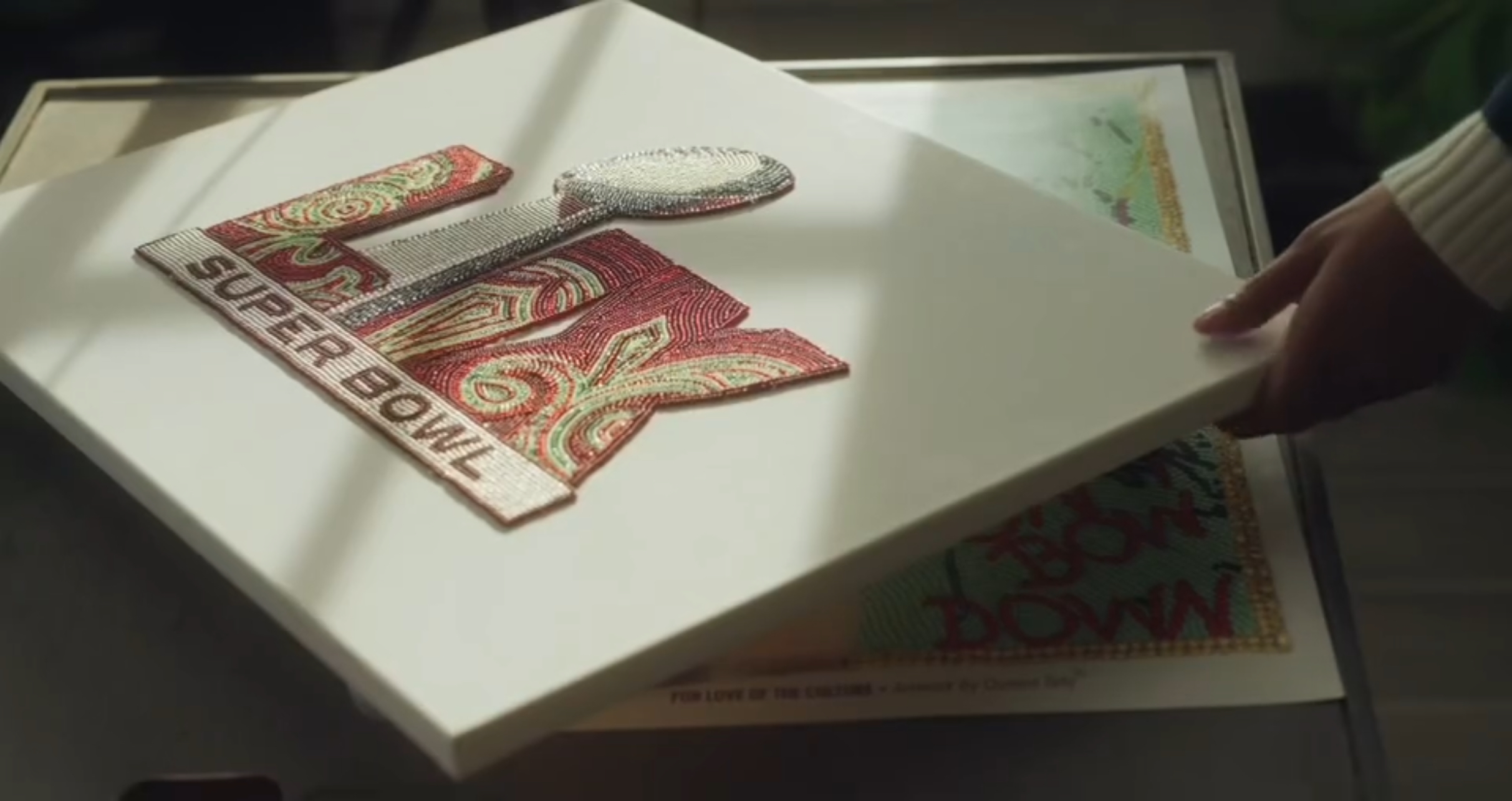

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’

Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’ Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month

Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball

The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

SUBMIT

CONNECT

Privacy Policy Copyright © 2025 Black Art Magazine is proudly powered by KVBOND