Black Art History

Exploring the lives and legacies of Black artists who shaped art history and culture. Each week during Black History Month, we highlight trailblazing figures whose works continue to inspire and redefine the creative landscape.

Discover their stories, learn their impact, and join the conversation. Read the history. Give us feedback.

What Is Tonalism? The Art Movement That Painted Mood and Mystery

Not quite Impressionism, not quite Realism—why Tonalism remains one of the most mesmerizing movements in art.

Edward Bannister, Untitled (sailboat in river), 1876

Imagine a landscape at dusk—muted grays, deep blues, and soft browns blending together, creating a dreamlike atmosphere. The details fade into a haze, leaving behind only an emotional impression. This is Tonalism, an American art movement that emerged in the late 19th century, known for its moody, meditative landscapes and restrained color palettes.

Tonalism may not be as famous as Impressionism or the Hudson River School, but its impact on American painting was profound. It laid the foundation for modern abstraction, influenced early photography, and shaped the work of artists like George Inness, James McNeill Whistler, and Edward Bannister.

The Essence of Tonalism: Mood Over Detail

Tonalism is less about depicting reality and more about evoking a feeling. Unlike the grand, dramatic landscapes of the Hudson River School, which celebrated nature’s vastness and clarity, Tonalist painters softened the edges, muted the contrasts, and focused on subtle gradations of light and color.

Key features of Tonalism:

• Limited color palettes – Earthy browns, deep greens, soft blues, and grays dominate.

• Blended forms – Objects and landscapes seem to dissolve into mist or shadow.

• Soft light and atmosphere – Often painted at dawn, dusk, or under moonlight.

• Emotional depth – The goal is not realism but mood—often peaceful, melancholic, or meditative.

Instead of dramatic mountain peaks or crisp rivers, Tonalist painters created quiet, poetic scenes that felt personal and introspective.

The Origins: A Reaction to Impressionism and Realism

Tonalism began in the 1880s and 1890s, largely as an American response to European art movements. While Impressionists in France focused on vibrant, sunlit colors and visible brushstrokes, Tonalists pulled back—choosing harmony and subtlety over brightness and movement.

The movement was heavily influenced by:

• The Barbizon School – A group of French painters, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, who emphasized mood and nature over grand historical scenes.

• Japanese Aesthetic Principles – The simplicity and atmospheric effects in Japanese prints inspired Tonalists to create compositions that felt balanced and meditative.

• James McNeill Whistler’s “Nocturnes” – Whistler’s moody, nearly abstract nighttime cityscapes set the stage for Tonalism’s focus on tone over detail.

In the U.S., Tonalism gained traction as artists like George Inness, Dwight Tryon, and Thomas Wilmer Dewing began using soft tones and minimal details to create atmospheric landscapes.

Key Tonalist Artists and Their Contributions

George Inness (1825–1894)

George Inness, Old Homestead, 1877, Haggin Museum, Stockton, CA

George Inness, Old Homestead, 1877, Haggin Museum, Stockton, CA

Inness is often considered the leading figure of American Tonalism. He was deeply influenced by the Barbizon School and believed art should express a spiritual connection to nature. His works, like The Home of the Heron (1893), use soft edges, misty fields, and delicate lighting to evoke an almost mystical mood.

James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne, 1880, etching print

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne, 1880, etching print

Though associated with Aestheticism, Whistler’s famous Nocturnes—dreamy, atmospheric cityscapes—align closely with Tonalist principles. His emphasis on harmony, abstraction, and mood over detail set the stage for modernist approaches to painting.

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

Dwight William Tryon, Daybreak, Fairhaven, 1885, painting

Dwight William Tryon, Daybreak, Fairhaven, 1885, painting

Tryon was one of the most dedicated Tonalist painters, known for his quiet, ethereal renderings of dawn and dusk landscapes. His works often depict fields and forests bathed in soft, diffused light.

Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938)

Thomas Wilmer Dewing, The Recitation, 1891

Thomas Wilmer Dewing, The Recitation, 1891

Dewing merged Tonalism with figure painting, creating dreamlike portraits of women in hazy, atmospheric settings. His approach combined symbolism, mood, and abstraction, bridging the gap between traditional portraiture and modernist experimentation.

John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902)

John Henry Twachtman, Icebound, 1889, Medium oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago

John Henry Twachtman, Icebound, 1889, Medium oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago

Twachtman’s work blended Impressionism and Tonalism. His winter landscapes showcase the blurring of form and muted color palettes that defined the movement.

Edward Mitchell Bannister (1828–1901)

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Streamside, 1870, oil on canvas

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Streamside, 1870, oil on canvas

One of the few Black artists to gain recognition in the 19th century, Bannister adopted Tonalist techniques in his landscape paintings, emphasizing earthy hues, atmosphere, and spiritual depth. His works, such as Streamside (1870), reflect a deep reverence for nature and a poetic sense of quiet.

Bannister’s approach was significant because it allowed Black artists to engage in mainstream artistic movements without being confined to racialized subject matter.

Tonalism’s Legacy and Influence on Modern Art

By the early 20th century, Tonalism began to fade as Impressionism and Modernism gained dominance. However, its influence can still be seen in:

• Abstract Expressionism – Artists like Mark Rothko built on Tonalism’s focus on mood and color harmony.

• Pictorialist Photography – Early photographers like Edward Steichen used soft focus and atmospheric lighting, mimicking Tonalist techniques.

• Contemporary Minimalism – Modern landscape painters still use Tonalist principles to evoke emotion through simplicity and tone.

Today, museums like the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Rhode Island School of Design Museum hold Tonalist works, showcasing the movement’s lasting impact.

In a world dominated by bright screens and overstimulation, Tonalism’s quiet, introspective nature feels almost revolutionary. It reminds us that art doesn’t have to shout—it can whisper, linger, and invite us into a moment of reflection.

What do you think? Does Tonalism’s subtlety resonate with you, or do you prefer more vibrant styles? Let’s discuss.

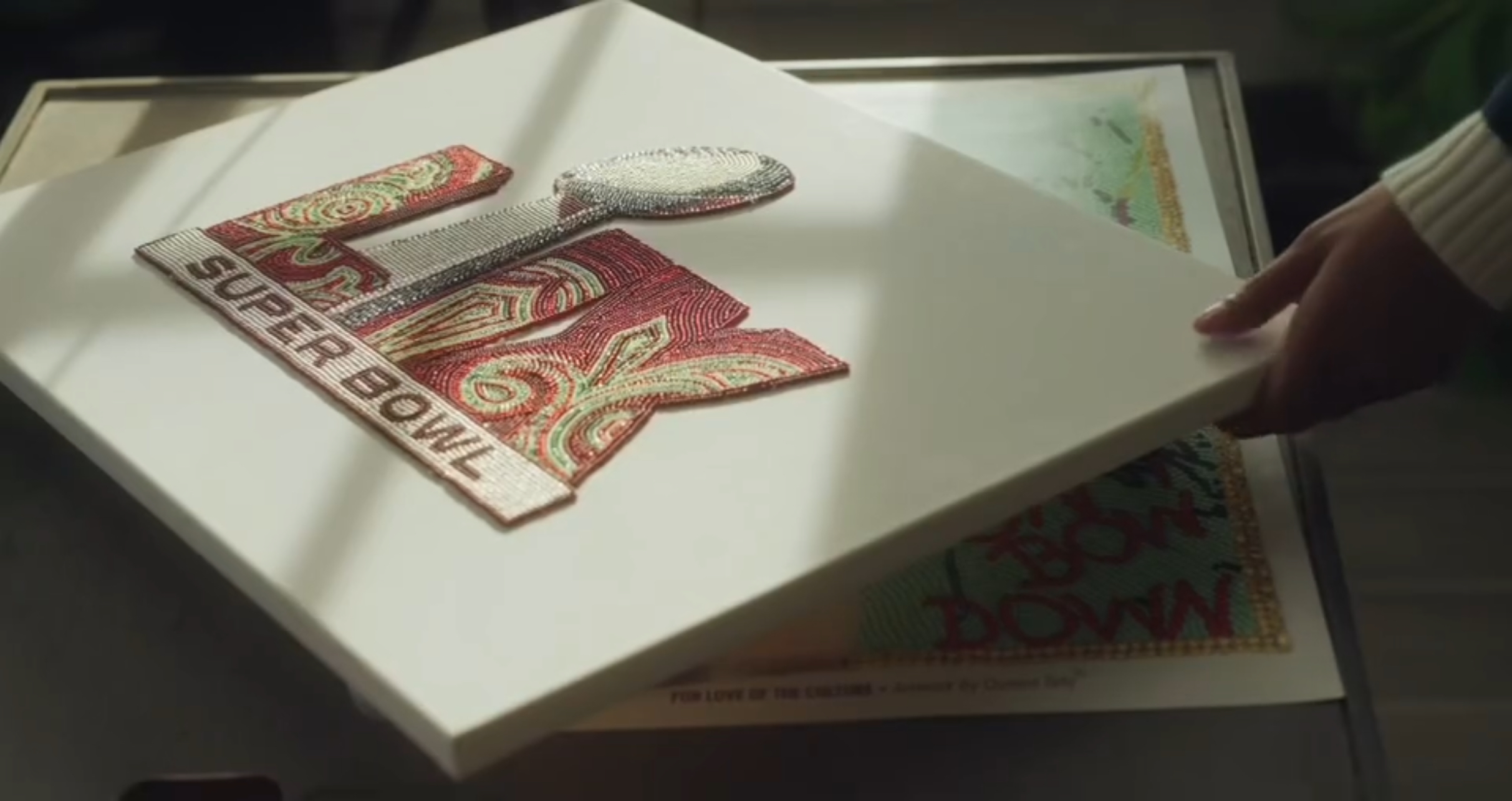

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’

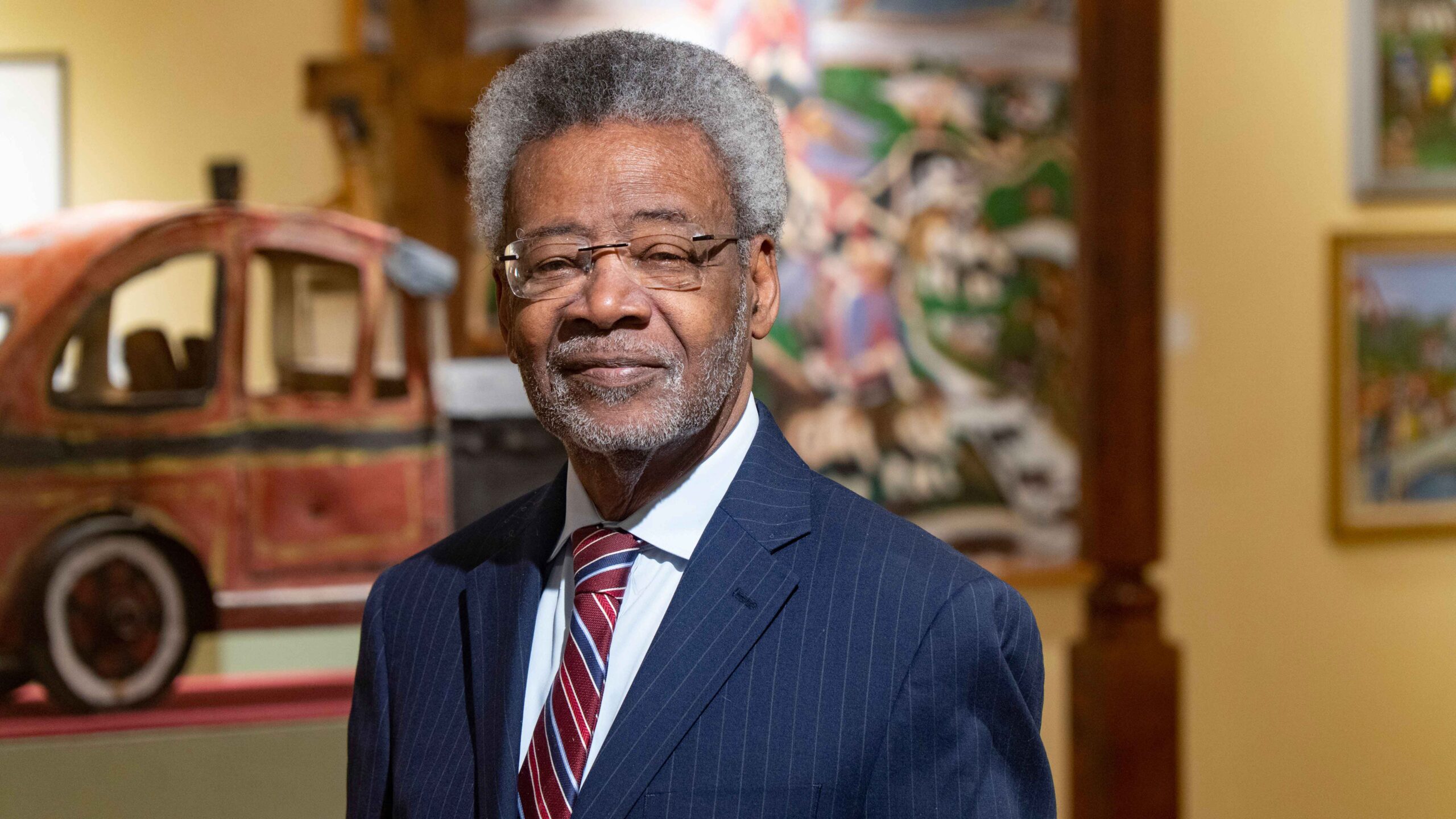

Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’ Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month

Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball

The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

SUBMIT

CONNECT

Privacy Policy Copyright © 2025 Black Art Magazine is proudly powered by KVBOND