Black Art History

Exploring the lives and legacies of Black artists who shaped art history and culture. Each week during Black History Month, we highlight trailblazing figures whose works continue to inspire and redefine the creative landscape.

Discover their stories, learn their impact, and join the conversation. Read the history. Give us feedback.

Jacob Lawrence: The Storyteller of Black Life in Motion

Through vivid colors and striking compositions, Jacob Lawrence captured the movement, resilience, and history of Black life in America.

Jacob Lawrence, The Library, 1960, tempera on fiberboard, 24 x 29 7/8 in. (60.9 x 75.8 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc., 1969.47.24

Jacob Lawrence painted stories with the precision of a historian and the energy of a storyteller. His work carried the weight of migration, labor, and resilience, built from sharp angles and bold color. He didn’t work in single images—his paintings formed sequences, like chapters in a book, unfolding movement by movement.

Born in 1917 in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Lawrence moved to Harlem at a crucial moment in Black cultural history. The Harlem Renaissance was in full force, shaping his worldview before he even picked up a brush. He trained under Augusta Savage and Charles Alston, absorbing the influence of writers, musicians, and intellectuals who passed through the neighborhood’s studios and salons. Harlem offered him more than artistic training. It gave him material—real lives, struggles, and ambitions to document.

By the time he was 23, Lawrence had completed The Migration Series, a 60-panel account of Black Americans leaving the South for the industrial cities of the North. The series was a landmark. The Museum of Modern Art and The Phillips Collection divided the paintings between them, making him one of the first Black artists to gain major institutional recognition. Fortune magazine ran 26 panels in color, putting his work in front of a national audience. The series was ambitious, but it wasn’t abstract. Lawrence built it from real accounts, studying historical records and speaking with those who had lived the migration.

A Style That Moved

Lawrence worked in what he called “dynamic cubism,” breaking figures into angular forms and layering color in a way that created momentum. His compositions often leaned forward, structured like a continuous rhythm. The design of The Migration Series wasn’t accidental—he made every panel the same size, used the same color palette across all 60, and planned them in sequence so they felt like they belonged together. The captions reinforced that structure, delivering history in short, declarative lines.

“The migrants arrived in great numbers.”

“The railroad stations were crowded with migrants.”

“And the migrants kept coming.”

The impact was immediate. Viewers didn’t just see history—they felt its movement, its inevitability.

Jacob Lawrence, The migrants arrived in great numbers, 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 × 18 in. (30.5 × 45.7 cm). The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Photo: Ron Cogswell, CC BY 2.0.

Jacob Lawrence, The migrants arrived in great numbers, 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 × 18 in. (30.5 × 45.7 cm). The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Photo: Ron Cogswell, CC BY 2.0.

Telling History on His Own Terms

Lawrence returned to historical storytelling throughout his career, creating series on Toussaint Louverture, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and John Brown. His paintings emphasized leadership as a shared effort rather than the work of singular heroes. The people in his compositions acted together, whether escaping enslavement, building cities, or protesting injustice.

In Struggle: From the History of the American People (1954–56), he widened his focus beyond Black history and painted key moments in American history. The perspective remained clear—he framed history from the view of workers, soldiers, and those on the margins rather than presidents and generals. One panel in the series shows an unnamed Black soldier in the American Revolution, bayonet raised, locked in combat. The image served as a reminder that Black Americans had fought for freedom in wars long before they were recognized as full citizens.

A Legacy That Still Moves

The influence of Lawrence’s work stretches across generations. Kerry James Marshall has cited him as a foundational influence. Contemporary artists continue to build on his storytelling approach, treating history as a subject that demands engagement rather than nostalgia. The Builders series, which Lawrence painted later in his career, focused on labor and construction, reinforcing his lifelong belief in progress as something actively created rather than passively experienced.

Many artists tell history, but Lawrence designed a structure for it. He built a visual language that made movement and struggle tangible. His compositions didn’t capture isolated moments—they formed a continuous, evolving conversation. The way he told history still feels immediate because the forces he painted never stopped.

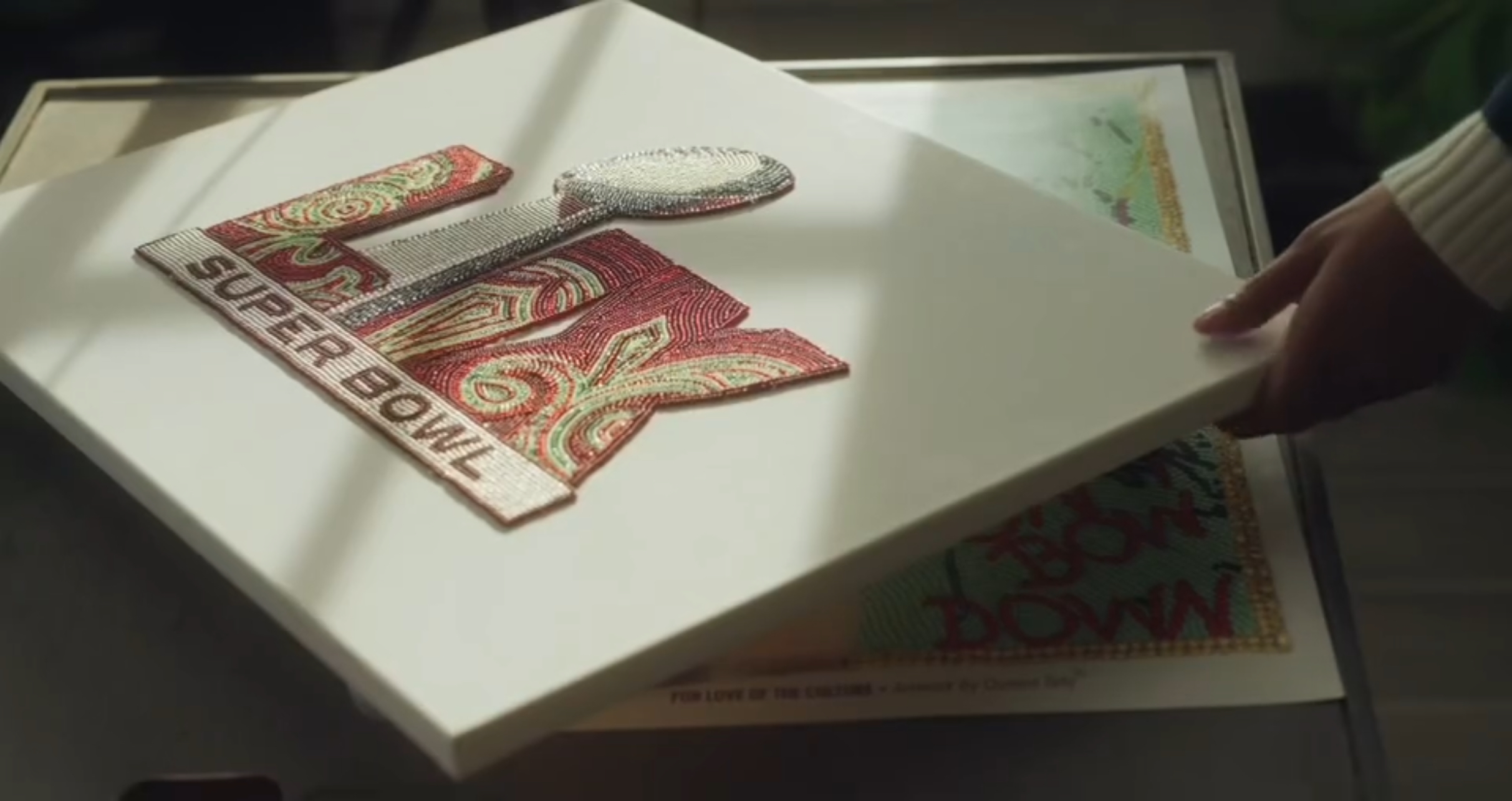

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’

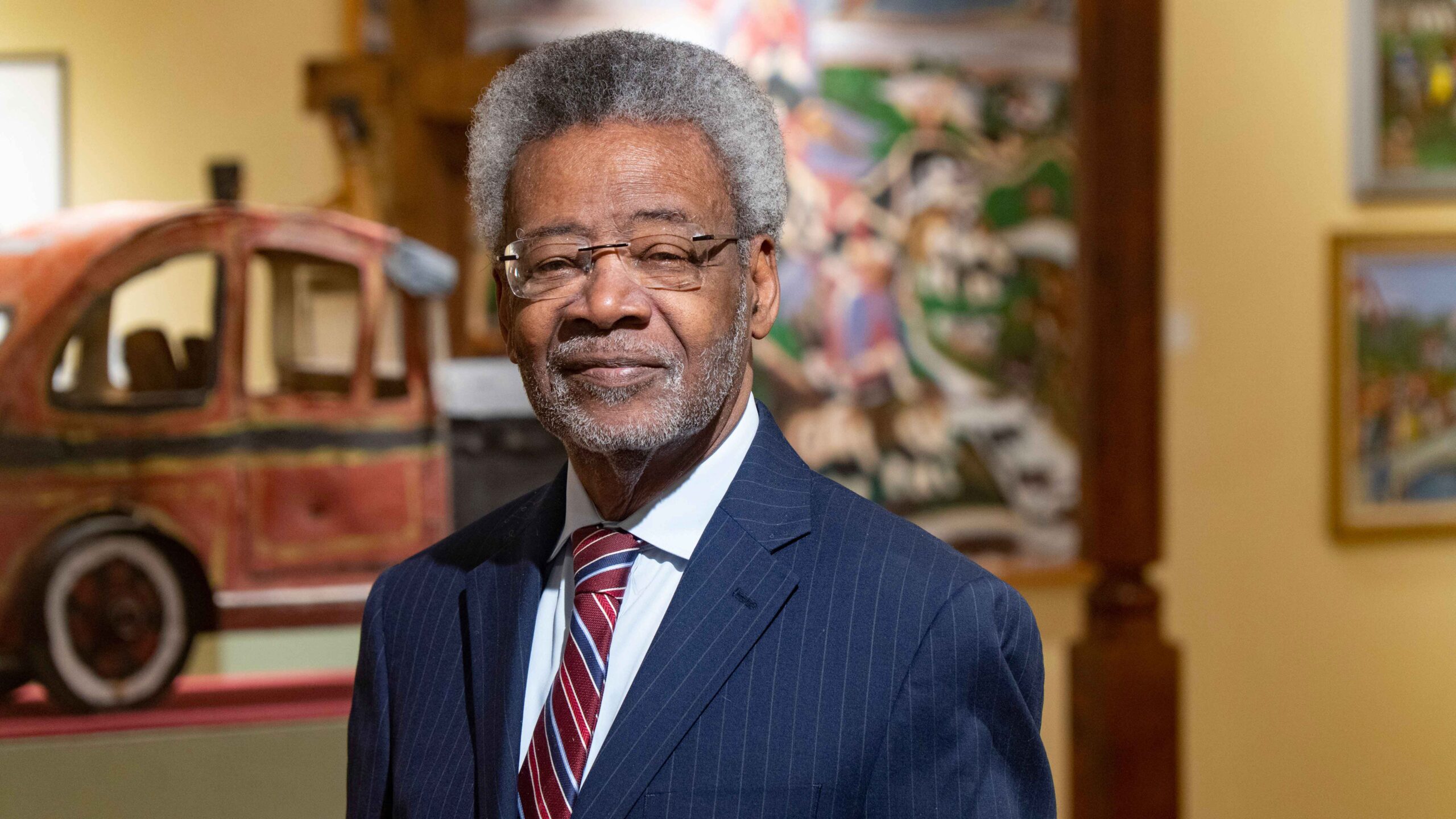

Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’ Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month

Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball

The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

SUBMIT

CONNECT

Privacy Policy Copyright © 2025 Black Art Magazine is proudly powered by KVBOND