Black Art History

Exploring the lives and legacies of Black artists who shaped art history and culture. Each week during Black History Month, we highlight trailblazing figures whose works continue to inspire and redefine the creative landscape.

Discover their stories, learn their impact, and join the conversation. Read the history. Give us feedback.

Horace Pippin: The Self-Taught Painter Who Captured Black Life and War

Horace Pippin, a self-taught artist and World War I veteran, overcame physical disability to create powerful works that depicted African American life, historical events, and themes of resilience and faith. His paintings remain a testament to the enduring power of storytelling through art.

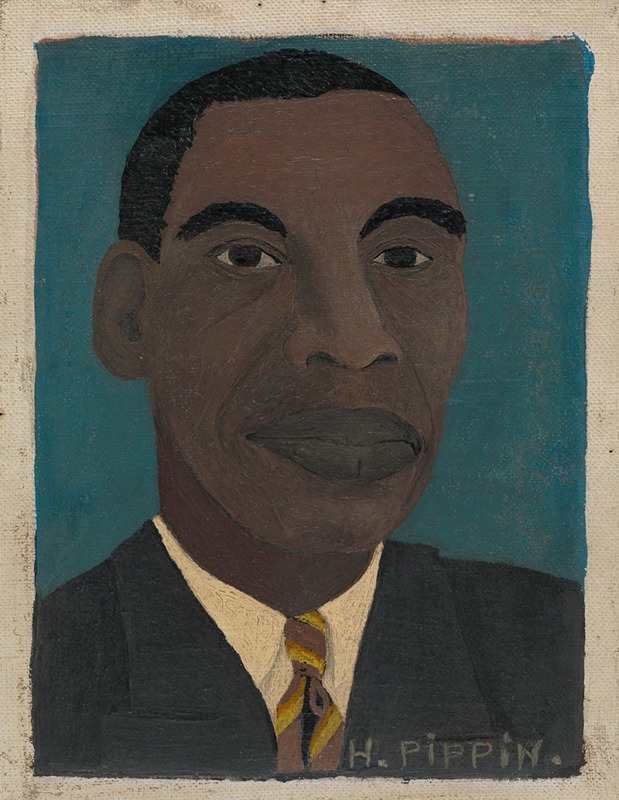

Horace Pippin, Self-Portrait II, 1944, Oil on canvas, adhered to cardboard

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Horace Pippin was born in 1888 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and spent much of his early life in New York. From a young age, he showed a natural talent for drawing, often sketching scenes from memory. Without access to formal training, he developed his skills through observation and practice. Art became a constant presence in his life, but it wasn’t until later that he fully committed to painting.

War and the Struggle to Paint Again

Pippin’s path took an unexpected turn when he served in World War I as part of the Harlem Hellfighters, a distinguished all-Black regiment. During combat in France, he was shot in the right shoulder, leaving his arm permanently impaired. Many would have given up painting altogether, but Pippin found a way forward. He adapted by using his left hand to guide his right, gradually regaining control over his movements. His determination to create never faded, even when physical limitations made it difficult.

A Unique Artistic Voice Emerges

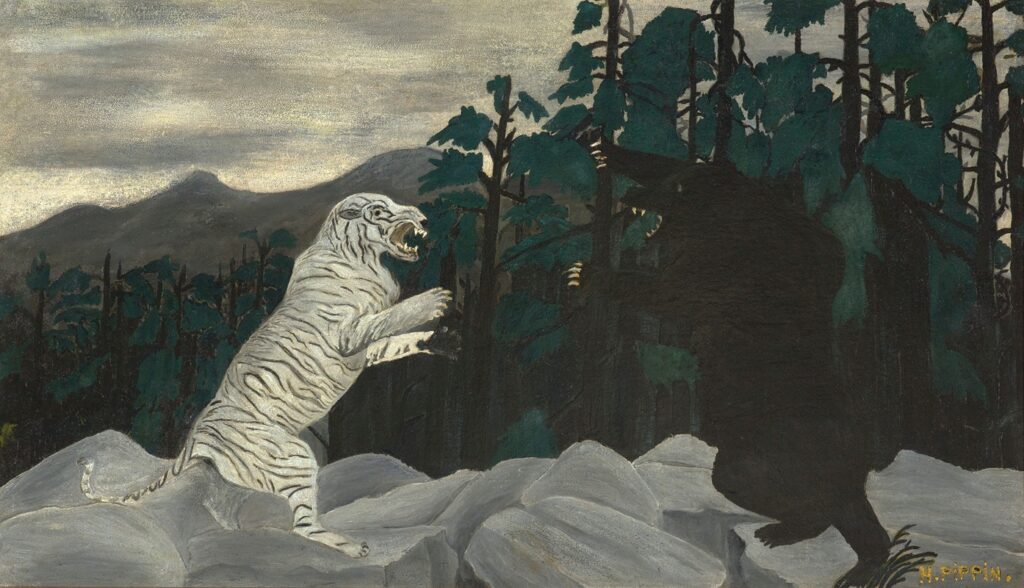

Horace Pippin, The Blue Tiger, 1933-1937, Oil on fabric

Horace Pippin, The Blue Tiger, 1933-1937, Oil on fabric

Pippin’s work was deeply personal. His first major painting, The End of the War: Starting Home (1930–33), depicted soldiers in the trenches, navigating a dark and smoky battlefield. Unlike the heroic war paintings of the time, Pippin’s portrayal of war was stark, human, and unflinching. His lived experience was always at the center of his work, making each painting feel intimate and urgent.

But war was only one part of his artistic vision. Pippin painted a broad range of subjects, from Black family life to historical figures like Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist John Brown. His ability to merge personal memory with broader cultural narratives gave his work a singular power. In pieces like Domino Players (1943), he captured quiet, everyday moments with striking emotional depth. The figures, often outlined in bold black strokes, carried a weight that made them feel monumental.

The Significance of His Artistry

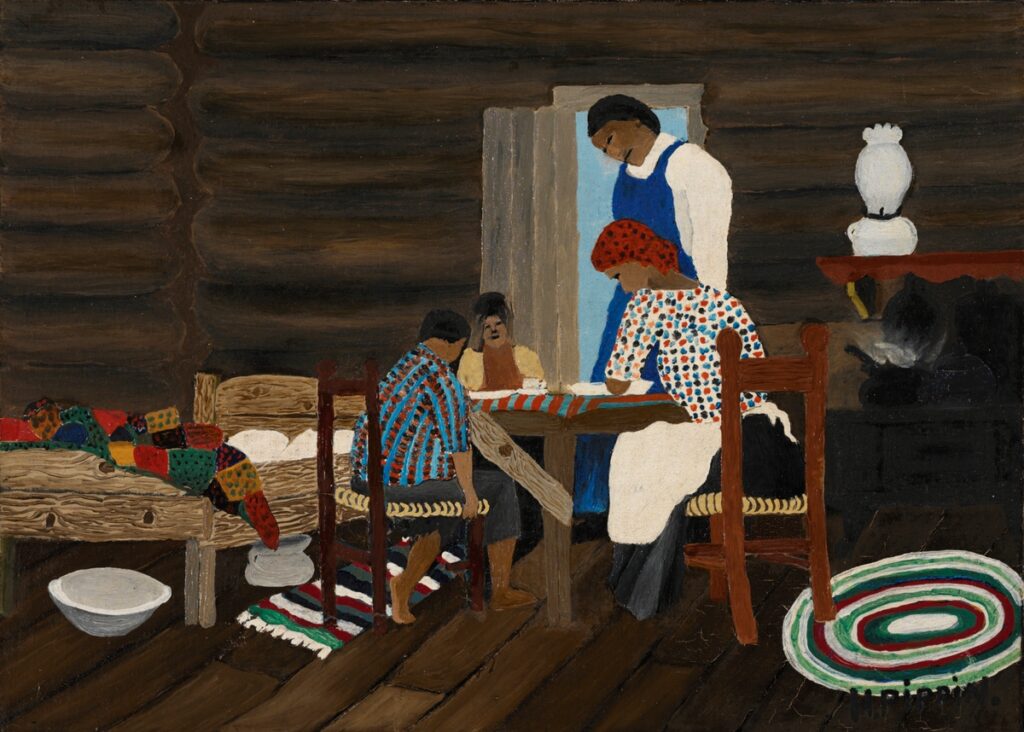

Horace Pippin, Giving Thanks, 1942, Oil on canvas (later mounted to composition board)

Horace Pippin, Giving Thanks, 1942, Oil on canvas (later mounted to composition board)

Pippin’s paintings broke barriers in the art world, offering a perspective rarely seen in mainstream American art. As a self-taught artist, he worked outside of academic traditions, yet his work held a sophistication that challenged assumptions about what “folk” or “primitive” art could be. His style combined flatness with depth, simplicity with complexity, and personal history with social critique.

One of his most compelling paintings, Mr. Prejudice (1943), directly confronted racism. The composition featured a white figure driving a wedge between Black and white figures, symbolizing the systemic forces that divided American society. Through stark symbolism, Pippin made his stance clear—Black soldiers had fought for their country, yet they returned to a nation that still denied them full rights. His work did not shy away from hard truths, making him one of the most politically significant artists of his time.

Recognition and Lasting Influence

Horace Pippin, Old Black Joe, 1943, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in. (61.0 x 76.1 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 1999.23

Horace Pippin, Old Black Joe, 1943, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in. (61.0 x 76.1 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 1999.23

Recognition came late in Pippin’s life. In the 1940s, museums and collectors began to take notice. The Barnes Foundation championed his work, and exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art helped establish his place in American art history. Though his career in the spotlight was short-lived, his influence was lasting.

Pippin’s art paved the way for later generations of Black artists who sought to tell their own stories, in their own way. His paintings remain in major museum collections, serving as a reminder that true artistry does not require formal training—it requires vision, authenticity, and an unwavering commitment to one’s truth.

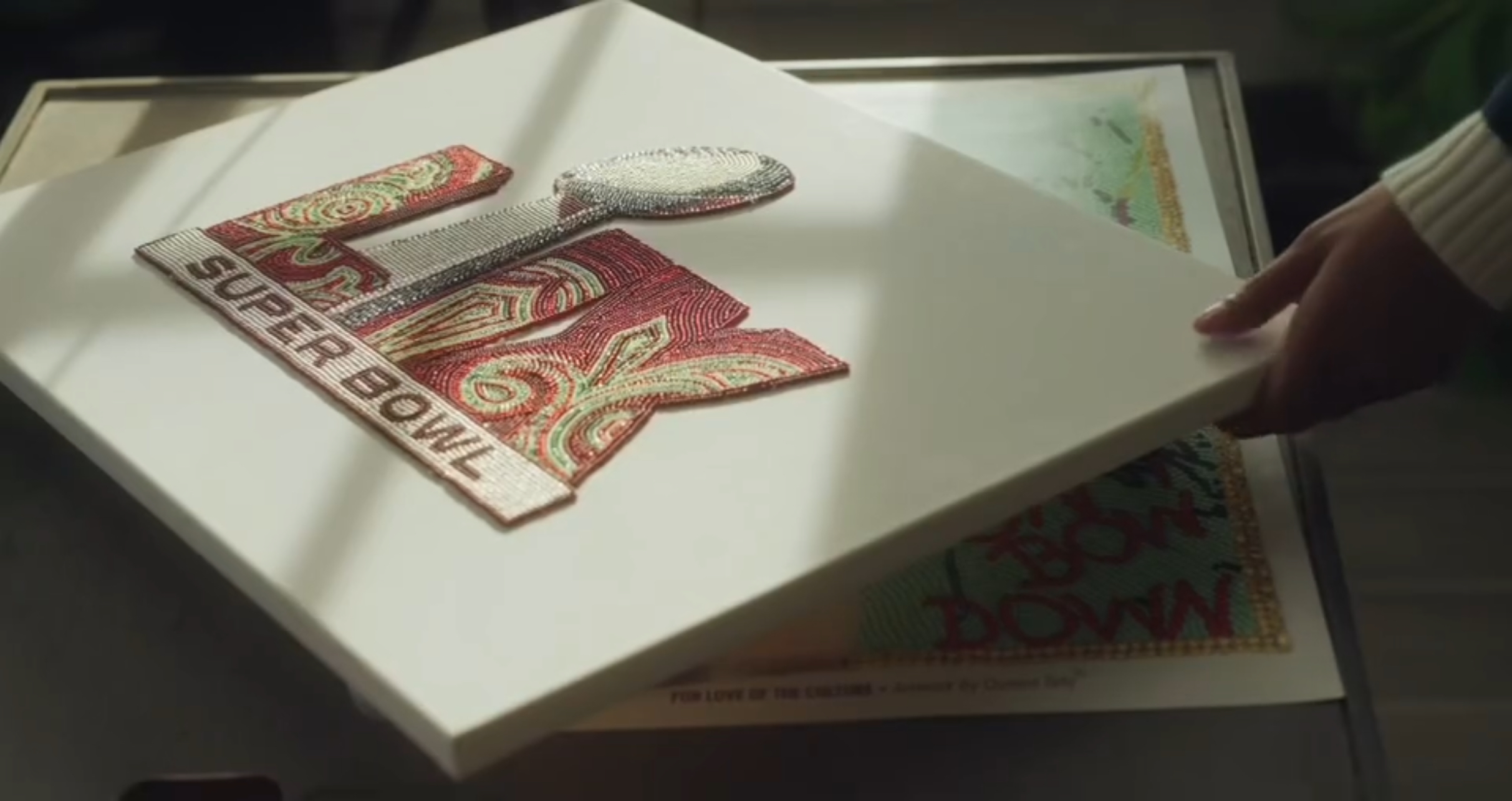

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo

“Queen Tahj” Williams: The First Black Woman to Design the Official Super Bowl Logo Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’

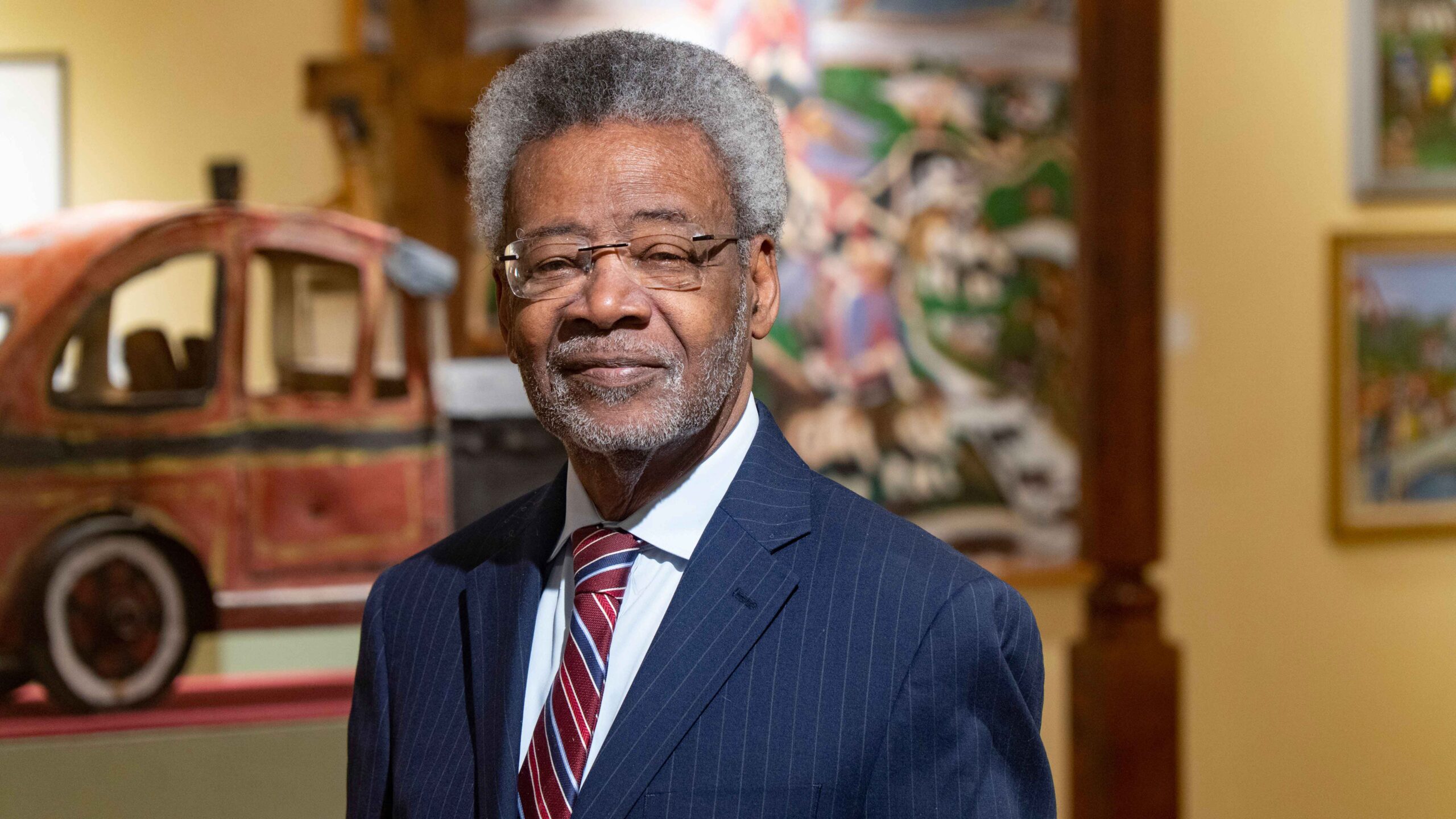

Lancaster Art Vault Exhibits Black Art with ‘Expressions of Strength’ Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month

Dallas’ African American Museum Kicks Off Black History Month The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball

The African American Museum in Dallas Marks 50 Years with Founders Ball Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

Koyo Kouoh’s Appointment as 2026 Venice Biennale Curator

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

SUBMIT

CONNECT

Privacy Policy Copyright © 2025 Black Art Magazine is proudly powered by KVBOND