Table of Contents

- Meet Tiara Kinnebrew

- Interview with Carla Denise Byrd

- Meet Jay Delnegro

- Interview with Racquel Miller

- Interview with Marguerite Copeland

- Interview with Cherese Douglas

- Interview with Kirsten Campbell

- Interview with Austen Brantley

- Meet Deka Henry

- Casta: The Origins of Caste by Yıldız Öztürk

- Meet Kiera Rahming-Reed

- Interview with Ofobuike Okudoh

- Thread My Needle by Erik La Prade

- Meet Vaniza Pierre

- Meet Keadra Jeter

- Interview with Dany Green

- Meet Kendra Monice Hansford

- Meet Karin Bond

- Meet Tomiwa Adelagun

- Interview with Charmaine French

- Interview with Elisha Nyong

Thread My Needle by Erik La Prade

Thread My Needle

A Quilting Group Brings Together an Alabama Community One Thread at a Time

By Erik La Prade

During a visit to Wetumpka, Alabama in May 2023, I went to the Black History Museum, where a group of women gather each Tuesday of the week to meet and quilt together. The women in the Thread My Needle quilting group generally number between six and ten, of varying ages.

During a visit to Wetumpka, Alabama in May 2023, I went to the Black History Museum, where a group of women gather each Tuesday of the week to meet and quilt together. The women in the Thread My Needle quilting group generally number between six and ten, of varying ages.

Some of the original members have died since the group began meeting in the Museum over twenty years ago. Lately, however, a number of younger women, interested in learning how to make a quilt, have joined the group. Certainly, the interest of the next generation in learning this folk art is central to the group’s continuing longevity.

I first encountered this group of ladies in 2003. It was because of one of my relatives that I visited Wetumpka that year. Scott Jones, a great-uncle of mine, had left Wetumpka when he was sixteen to avoid being jailed and put on a work gang. He traveled as far as Green River, Wyoming. His wife had died when he was young and he spent much of his life working in various hotels, visiting one relative or another. As another uncle told me, “Scott was lucky he owned a pair of shoes.”

I had originally met him on a visit to Miami in 2000 when he was one hundred years old. At that time, he was thin and short and walked with a cane, but he had a quick step and moved gracefully. He took me to his favorite restaurant: a nondescript local sit-down place. His “regular” waitress served him. She was very fond of Scott and made a fuss over him. Besides women, Scott loved baseball and cigars, and before meeting him for lunch, I bought a twelve-dollar cigar which I gave him. During lunch, he drank black coffee and ate spinach and mashed potatoes.

He asked me about my father and a few other relatives. He asked me if, when he died, I could take his ashes and bury them in a family plot located in Wetumpka’s city cemetery. I promised him that I would. He died in 2003 at one hundred and three years old.

After he died, a cousin and I flew down to Miami, settled what little existed of his effects, and arranged for his body to be cremated. We took his ashes back to New York. I contacted a local funeral parlor in Wetumpka and paid for a footstone to be made for my Uncle Scott. About a month later I went to Wetumpka, with the ashes, arriving there on a Saturday. The next day, I met with the director of the funeral parlor and we drove to my family’s plot in the city cemetery, where I picked out a spot near to where Scott’s mother was buried. A hole was dug and I placed the urn in the hole. After the hole was covered, the footstone was set into place.

Along with the funeral parlor director and his workers, I was joined by a great cousin named Savannah Peak, whose parents Maud and Louie Peak were buried nearby in the same cemetery. After the burial, Savannah and I ate lunch and she drove me around the town, picking out places for me to visit and photograph while talking non-stop about various people in Wetumpka, both the living and the dead.

The day after Scott’s burial, I got up in the morning and walked from my hotel to the Black History Museum, (the historic Rosenwald School) about two miles away. I knocked on the door and entered the building. A group of women were in the same room in which some of them had once attended grammar school. On one side of the room was a display of several quilts, folded over and neatly hanging down from the metal arm of a display stand. Each quilt had a different pattern and I found myself intrigued by their designs. Then I wandered around in the other room of the school.

The contrast between the women, who were busily quilting in one room, and the displays and objects in the other room, was striking. The women made the history of this building come to life for me, but the museum objects – including original school writing desks and a set of cotton counterweights for measuring the weight of bales of cotton placed on a scale – presented another side of the history of this community.

During my latest visit in 2023, Jackie Lacey, who is one of the founders of the Thread My Needle group, demonstrated for me just exactly how she threads her needle:

“We double the two ends of the thread and pull it through the needle together. Then make a knot and pull it through the fabric and sew it. We pull that knot between the three pieces (of a quilt), and you probably won’t be able to find where it started and where it finished. It’s one piece.”

Working together as a group, the quilters sit around a large quilt-frame with the parts of a queen-size or king-size quilt spread across it. The frame supports the material which is to be sewn together. All three parts of the quilt are held in place as they are stretched across the frame; the top with the pieced pattern; the middle padding; and the backing, and all have to be made even.

Some of the women work at home making top sections from pieces they have there and then bring them in so that they can be pieced together to make the quilt tops. Jackie generally makes tops at home in the summer when it is too hot to lay a whole padded quilt across her lap to work on it. This heavier work she saves for the autumn and winter. Each woman hand-sews a different area of the quilt in progress, until all three parts, the top, the padding and the backing are evenly squared off and joined together as one. Then Jackie hand-sews a border along the edge of each quilt.

The community of Wallsboro, where Jackie grew up and learned quilting, was a strong, predominantly Black community. Historically, Wallsboro was a post-Civil War community where Black families owned and worked on their pieces of farmland growing food for themselves and also to sell.

Jackie Lacey was born in Wallsboro and currently lives about two miles from where she was born. She told me how her mother would take her to a quilting group in Wallsboro when she was a young girl: “I learned how to thread my needle and how to use a thimble . . . I watched the ladies and my mom sewing, and then, I learned.”

In a later conversation with me, Jackie related how those same ladies, “knew how to take care of everything.” One of the things they took care of was their gardens: “Everyone had a garden and when the apples and rutabaga and corn was ripe, the women would get together and exchange them . . . I had my own garden when I got grown because I had to have something to eat and feed my children.”

The women Jackie knew as a child while growing up in Wallsboro mostly lived on farms and had time to quilt – when they weren’t working in the fields or cooking at night, they would spend about two hours making quilts.

“Back then, what we were doing was making quilts to keep warm in the winter. We’d use anything – old dresses, torn-up overalls, fabric – make a pattern and put it together . . . I wish I had saved some of my mother’s quilts, but I never thought about keeping some for years to come.”

While quilting is historically viewed as a group activity, I saw it as one reason this Black community, past and present, survived: because they were, and are, self-sufficient. The quilts these women make are metaphors for how this community was able to survive by coming together.

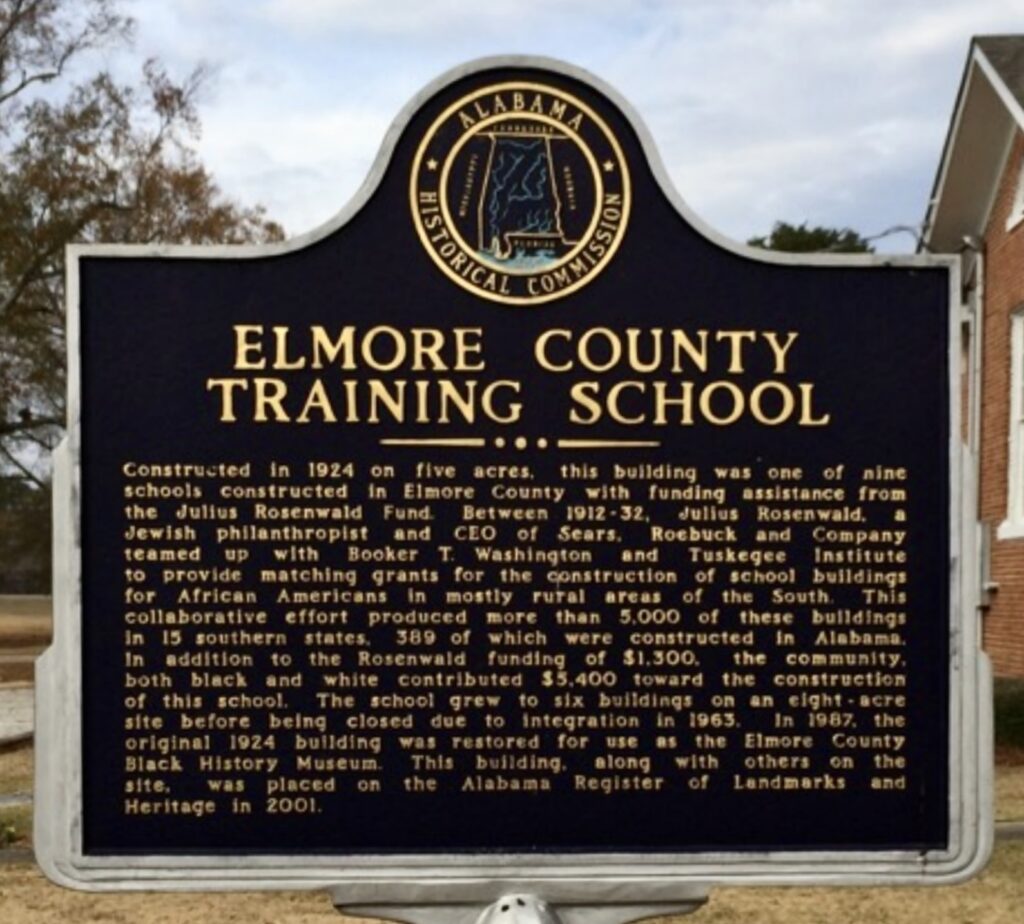

Near the front of the Black History Museum building, there is a stand-alone metal marker about five feet high on a pole. This marker was placed there by the Alabama Historical Commission, designating it as a historical building, and it acts as a label explaining the history of the school and the building.

The school, called the Elmore County Training School, was the result of the collaboration between Julius Rosenwald, a Jewish philanthropist and CEO of Sears Roebuck and Company, and Booker T. Washington, the scientist, writer, and founder of the Tuskegee Institute. The Rosenwald Schools were built between 1912 and 1932, and this particular school was built in 1924, as one of five buildings. Behind the brick school was a wooden building, the teachers’ residence, where the teachers lived during the weekdays.

Most Rosenwald schools were closed in 1954 when segregation was declared illegal by the Supreme Court. According to the marker for the Elmore County Training School, it closed in 1963, as integration between Black and white students normalized the educational environment. In 1987, this building was restored and began to function as the Elmore County Black History Museum.

There is a curious informational gap on this historical marker, which I became aware of after reading the following sentence several times over: “The school grew to six buildings on an eight-acre site before being closed due to integration in 1963.” While segregation had been declared illegal nine years before by the Supreme Court, why did this school continue to function?

I asked Jackie about this and she informed me, “Some of the Black children still stayed and went to the Elmore County Training School, and some went to the white high school. Some of the Black students were afraid to go to the white school and their parents didn’t want them to go there. What happened was, the Klansmen put up and burned crosses around Wetumpka. The white people didn’t want the children there and the Black children were scared to go to school. Most of the Black children in Wetumpka that walked to school, went to the Training School.” When I asked who taught there she told me, “some of the same teachers.”

But, in 1963, “the school was closed down and the Black students went to the high school.” Several years later, the city built a new high school so all the students could attend it together. When Jackie attended the Training School, from the ninth to the eleventh grades, she told me they had classes, particularly home economics, which included sewing to “make different garments,” but “quilting was going on in the home but not in the school.”

Not all the women in the Thread My Needle group attended the Elmore County Training School which was located in this building. But there is something historically resonant when you consider that many of these women did go to school here, and are now creating quilts commemorating their own history in this space which was once a segregated school. Jackie told me, “We’re proud of having gone to school here.”

_________________________

A major figure in the history of the Elmore County Training School was Mr. Weldon Doby, who served at the school as both teacher and principal. Doby graduated from Wilberforce University and the University of Cincinnati and began teaching at the school in 1930, continuing there for twenty-seven years, and helping the teachers and the school to gain accreditation.

A group photograph taken in front of the Elmore County Training School provides an historical record of Doby gathered together with a group of teachers, parents, students and former students. The specific occasion for this gathering is not recorded, but it appears to date from the late 1940s to early 1950s.

Doby wears a grey suit and stands on the far left of the picture, handing a piece of paper to the woman second from the left in the front row. It is possible this photo was taken to commemorate the school receiving accreditation.

There is one teacher standing in the back row to the right of the entrance, next to the small window. Her name is Eloyse Jones (1911-2005). She was a lifelong resident of Wetumpka (and also my great-aunt, and cousin to Mr. Scott Jones). She went to Alabama State University and Tuskegee Institute, and taught home economics at the Training School for over thirty years. Later, when the schools were integrated, Eloyse taught at the Wetumpka High School. She was Jackie Lacey’s teacher from the ninth to the eleventh grade.

The curator of the Black History Museum is a woman named Billie Rawls, who is also a member of the quilting group. Billie originally volunteered to work in the Museum about twenty-two years ago, eventually becoming the full-time curator. Now, she curates and organizes the various collections in the building and new materials that are periodically donated. Sometimes she visits the homes of recently deceased Wetumpka residents to retrieve documents, letters, photographs and physical items (such as school seats) relating to Black history, both those specific to Wetumpka and those of general interest.

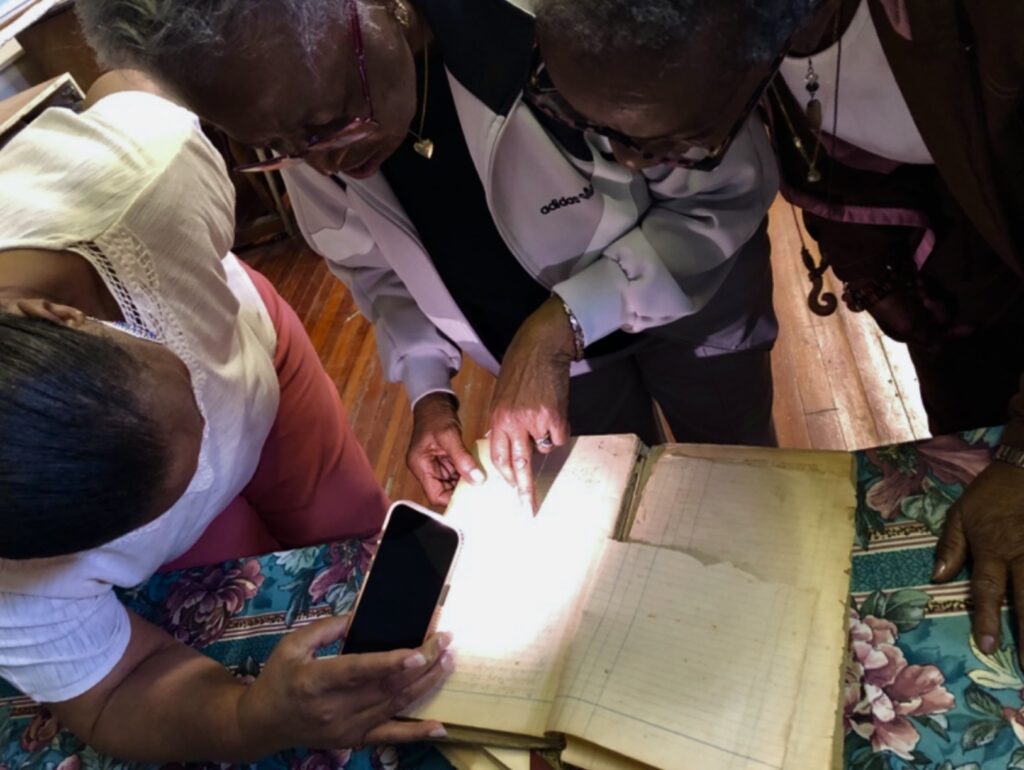

One set of papers Billie acquired are the record books once kept by the county farm agent, Mr. Roscoe Lee (1909 -1989). Lee attended and graduated from Tuskegee Institute. He was an important figure in Elmore County, who worked with the local farmers, instructing them on the best crops to rotate to enrich the soil, and on a range of other farm issues. He and his wife, Dot Lee, were well-known in Wetumpka.

Billie told me that her “long-range goal for the museum is to eventually begin accepting and archiving large collections, and to apply for grant money from a number of foundations to maintain the museum’s archives.”

In the early 1980s, the city was planning to tear down the building. But, in 1986, “several remarkable River Region preservationists came together with a proposal to keep the building from being demolished. Former mayor Jeanette Barrett . . . [and] former retired Elmore County extension agent Roscoe A. Lee, with assistance from Mrs. Hertisene Crenshaw, located funds to renovate the historic but deteriorating facility.”

For the women in the Thread My Needle group, making quilts is not a necessity, but a personal pleasure reflecting their love of the work. I could not ascertain how many women in the group were introduced to quilting as children, but as adults, they had a desire to learn or continue it.

Originally, the quilting group consisted of only three women who met in Jackie Lacey’s house. It was Frazine Taylor, an archivist and teacher from Alabama State University who encouraged the group to move into the museum, and in 2000, the club had increased to 17 members.

Jackie wants hand quilting to continue and she is encouraged when younger women attend the group’s Tuesday meeting with an interest in learning how to quilt: “Some of them have never used a needle and they’re afraid of sticking their finger! Some have used a sewing machine so long, they can’t do it.” Jackie is aware of the more famous Gee’s Bend quilters. But she points out to me that they now use sewing machines to make quilts. To her, quilting should only be done by hand since that is how it was done originally, and she considers it a tradition that should be preserved and passed on.

One can see evidence of the many different hands which have worked on each quilt by closely examining the quilting stitches. Each worker has a slightly different style – some using larger, and some, smaller stitches, some so fine they look almost machine-made but aren’t. Jackie herself owns two sewing machines at home but never uses them for quilting and would never allow one to be used by the women in the quilting group.

She is also familiar with the quilts made by the Underground Railroad quilters, and likes to point out how each square in the pattern tells a story. She owns two design books with Underground Railroad patterns in them. She hopes one day to make an Underground Railroad quilt but has not yet started one because of other projects.

The quilters of the Underground Railroad are known today for the ingenious ways that they created symbolic and informational block patterns in their quilts, to help guide slaves to free states and out of slavery. Currently, some historians debate whether or not such quilts provided slaves with complicated plans embedded in these hand-sewn patterns. I suspect Jackie’s interest in creating an Underground Railroad quilt is both historical and artistic.

The group not only creates new quilts but also repairs old and “raggedy” ones. Jackie explained how a young man once brought them an old quilt his grandmother had made. He wanted them to repair it because there were some pieces in it that had come from his grandfather’s shirt. He didn’t care what the price was to repair it; clearly, it was a family heirloom. After repairing someone’s quilt, the group goes back to their own projects. As Jackie told me “We don’t go by time, we just do what comes up.”